THE BURDEN OF THE BALKANS

BY

M. EDITH DURHAM

CHAPTER XII

ELBASAN TO SKODRA

I DID not appear next morning till 8 a.m., which is considered in this land such an abnormally late hour that everyone hammered madly on my door, and thought I must be ill. The police had been waiting patiently for hours to arrange to take me on a friendly visit to the Muttasarif, an Albanian but recently appointed—a big, jovial, white-haired old boy, who said I was his adopted sister, and could not do too much for me. Even through an interpreter his conversation was interesting, full of quaint parables and pithy sayings. He loved his country, and told about its beauties and its strange wild peoples. He struck me as well fitted to cope with them, more especially as he is Albanian, for no foreigner ever seems to win the confidence of the mountain-man.

'The other nations are old,' he said; ' my poor Albania is a child among them. She has much to learn.'

He was anxious to encourage European visitors to the town and to open up traffic. I was to do anything I pleased, and to ask for as many guards as I liked. In the town it was quite safe; outside he would rather send someone with me. The village people were as tame as sheep in the bazar, but in their own villages they were a little wild, he said merrily.

Elbasan took its cue from the Muttasarif, and was extraordinarily kind, from the soldier who, when asked to show the way, came along and took me and my travelling companion for a walk, and flatly refused a backshish on the grounds that we were friends, to the Begs, who are the big landowners. Upon these I was told it was my duty to call. I had my doubts myself about it, but was assured that it was not etiquette for them to call on me, and that it would please them extremely to see the only Englishwoman who had been to Elbasan, as far as anyone knew.

It was correct to begin at the wealthiest and to proceed afterwards to the less rich. They were all, of course, amazed to see me, but exceedingly polite, and made me very welcome. All but one had succeeded in looking quite European. He had spoilt the effect with quite the most killing waistcoat the mind can imagine. A tall, soldierly, fair man was so like an Englishman that I should have taken him for one at first sight had I comeacross him in a foreign hotel. Their houses strove all to be European, and I saw with regret that European carpets and walls badly frescoed by foreign workmen were more á Ia mode than the panelled walls and native rugs that I had admired in humbler dwellings. They all owned large estates, and were said to be good landlords.

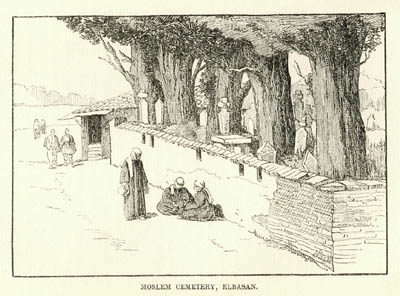

Elbasan has about 10,000 inhabitants; rather more than half are Moslems. The Christians are Orthodox, but the recent appointment to the district of a Greek Bishop, who is making great Hellenizing efforts in the schools, as successor to an Albanian one, has caused fierce discontent. Elbasan is tempted Romewards, and is striving hard for the establishment of an Uniate Church and school, in which teaching and preaching in the vernacular would be possible under Austrian protection. Could such a Church be established, I was told the Christian Albanians would go over to it almost in a body, and a number of Moslems would send their children to its school.

Patriotism flames in this district, and is far stronger than doctrinal religion. Much that I saw and heard indicated that, once freed from Turkish rule, whole villages that now call themselves Moslem would revert to Christianity at no distant date. Many Christians have declared themselves Romans. The Orthodox Church, they said, meant Russia, Greece, and tyranny; Rome means men trained in the West and civilization.

Elbasan's struggle for knowledge is very pathetic. You may find people who are bravely wrestling, unaided, with French and even German grammars. When it is remembered that no book can be imported into the Turkish Empire, except by smuggling, without passing the Turkish censor, which suspects everything it cannot understand, that no book can be sold that has not the stamp of the local Vali in it, and that before any book can be read these people have to learn a foreign language, the number of wellinformed and educated persons is very remarkable. The failure, so far, even with Austrian aid, to obtain the firman for the coveted Uniate Church and school is ascribed to Russia, who is said to terrorize the Sultan, and is hated with a hatred almost incredible in its virulence. In truth, the struggle in the Balkan Peninsula from some points of view is mainly AustroAlbanian versus Russo-Bulgarian, and anyonebetween is liable to be squashed. Albania vows that Russia encourages the absorption of South Albania by Greece, in order that Greece may be satisfied with territory there, and resign the rest of the Peninsula to be distributed according to Russian views.

The large number of Vlahs who live in and near Elbasan, here as elsewhere, are in favour of Albanian independence.

Elbasan does not merely talk. It was the only place where I was not told that 'the road was going to be made next year.' The road to Ochrida was already begun—-begun so elaborately, too, that I wondered if it could possibly keep up that standard and arrive at the other end. Elbasan covets roads to Durazzo and Berat as well, and is anxious for trade. It has already a soap factory that supplies all the neighbourhood with a very good article, made from olive oil, the crushed remains of the olive forming the fuel for boiling the soap, which is thus very economically turned out. Elbasan dreams of a great future, and its central situation would make it admirably suited for the capital of the country.

Town life and country life are not the same thing I had but just missed some local colour on the Berat track. News came in of a shooting affair the morning after I had passed. It was a characteristic and complicated tale of the Shpata district. A shepherd drove his flock to pasture on a tract of grass by that gravemarked path, but an hour's ride from the town. The owner came down and ordered him to go. The shepherd refused. Thereon the owner fired at him and missed, a thing you should never do in Albania. The shepherd then shot him dead, but was seen and recognised. Off went the gendarmerie hotfoot; the shepherd had been 'wanted' for some time. Ten years ago, as a lad of eighteen years, he had shot another youth dead. For this he was imprisoned at Elbasan. The police had a fit of activity, and the prison became so crowded that it was arranged to draft a number of prisoners down to Monastir, this lad among them. They were nearly all Shpatiotes. The convoy was ambushed by a rescue party from the wilds of Shpata, and a fierce fight, took place. The gendarmerie were beaten, and all the prisoners escaped. Apunitive expedition was sent up next day, and another battle took place at one of the mountain villages. The gendarmerie officer was killed, but four prisoners taken, all of them fresh ones. As the gendarmes were returning with them to Elbasan the escaped murderer (the shepherd of the Berat road) leapt up suddenly from behind a rock, shot a gendarme dead, and got clean away. The gendarmes, enraged by the deaths of both officer and comrades, shot all four prisoners dead there and then on the track, and there the affair ended. The shepherd was still at large when I left, and it was said he could not be taken without much bloodshed.

We talked of murder, violence, and brigandage. Things look very different in the East and the West. You may travel among the Balkan people alone, and drop for the time being every Western habit; you may eat with the natives, drink with them, sleep with them, ride with them, live as they do, and watch them patiently for months; you may visit and revisit their lands, and think that you are beginning to understand them, when something occurs that turns a sudden searchlight upon them, and you perceive in a flash that you were as far as ever from seeing things from their point of view. To do this you must leap back across the centuries, wipe the West and all its ideas from out of you, let loose all that there is in you of primitive man, and learn six languages, all quite useless in other parts of the world.

The difficulty, perhaps the impossibility, of this task is probably the reason why, up till the present, all intervention by the Western Powers, however well intentioned, has, when loosening one knot of the tangled skein of Balkan politics, generally succeeded only in tightening all the others.

The flashlight of revelation dies away, but afterwards the face of the land is changed. You cannot see it with Eastern eyes; you never again see it with Western ones. It occurs to you that when the revolution begins, you might borrow the kavas's revolver, and that there is someone you would like to get rid of. You know that the West would be scandalized by theideas that are surging through your mind. You are equally aware that the men with whom you are squatting round a wood fire would be shocked at your inability to go as far as they do.

You are in the greatest danger of finding yourself in the position of the man of whom it was said: 'Hit him hard ! He ain't got no friends!' And the flashlight episodes are often so far removed from Western ideas and experiences that it is almost waste of breath to talk about them, for the West thinks it knows better, and flatly refuses to believe in them; or the truth of the tale is proved beyond all doubt, and the West is so immeasurably shocked that it loses all sense of proportion and power of judgment, and blubbers hysterically, as it did, for instance, over Alexander and Draga. For the West has a short memory, and has forgotten the things it did but a few generations ago when it, too, was young: how it carried the heads of fellowcountrymen on pikes and stuck their quarters about the town; almost, if not quite, within living memory corpses rotted and stank on wayside gibbets even in England, and the heads of the Cato Street conspirators were hacked from their dead bodies in the year 1820.

And these are some of the things the West should remember, for in spite of them it has evolved a civilization that it admires so much that it wishes to force it on all the world. Through Western glasses the Shpata shepherd is seen as a mad dog, but he was explained otherwise to me.

He had played the game according to the code of his district. The first was an affair of honour; here a man's honour is very dear to him. His life is nothing compared to his honour. He was a Shpatiote; he followed the Albanian rule. But the Turkish Government put him in prison for it. In Shpata they do not recognise the right of the Turkish Government to interfere in their private affairs.

Afterwards, when he shot the gendarme, it was vengeance for those in the village who had been wounded and captured, and for his own wrongs. His last exploit upon the Berat road was not clearly explicable for want of details, but the other man had fired first, and had brought the consequences on himself. If he was to be avenged, it was the business of the dead man's family, and not of the TurkishGovernment. If there were an Albanian Government, that would be another thing. But the Turks !—no, thank you.

'You think in England you are civilized, and can teach us,' said someone passionately to me. 'I tell you there is no one here that would commit crimes such as are found in London. There you can find men who live by selling the honour of women. This has been printed in your own newspapers. You have no feeling of honour. How do you punish such a man ? You make him pay money and put him in prison! You let him live, and he is a disgrace to humanity. Bah ! we would shoot him like a wild beast ! Our brigands are poor men. By working hard in the fields they can only just live.

They are quite ignorant, and have never been to any school. They rob to live, and do so at the risk of their lives. But your brigands have often been to a university, and rob to obtain luxuries by lies and false promises. You have had all the advantages of education and civilization for years, and this is what you do. But you call us savages because we shoot people !' And it all depends upon the point of view.

I was eager to see the Shpatiotes at home. The Muttasarif sent the Police Commissary and two gendarmes with me, as he said the people were entirely unused to strangers; and we started early, that we might visit two villages and return before nightfall.

I was told not to hire a horse, as I was to be lent the best one in the town. It turned out to be a very handsome gray, and had it not been bitted with a curb that would hold leviathan, would have been very many sizes too good for me. It began by biting the tails of both the suvarris' horses, which promptly lashed out. The Police Commissary begged me to dismount and change to something quieter, but I felt it was quite impossible for Great Britain to climb down before Albania. Nevertheless, as my gallant mount pranced sideways down the street, snapping wildly at the leading suvarri's horse, I was almost forced to admit that 'L'Empire c'est moi' was an attitude I could not maintain. The animal, however, had a splendid action, and, after the first quarter of an hour, I never enjoyed a ride more.

We crossed Kurd Pasha's bridge, followed the river up-stream a little, and then struck into the Shpata district. It was a quite perfect spring day; the hillsides, well covered with copse-wood, were full of wildplum and cherry allblossoming, and the ground was gay with big butterfly and bee orchises. As for the lizards, they were the fattest and greenest I have ever met. The valley was but feebly cultivated. Men in cartridge-belts and fustanellas were guiding their primitive ploughs—crooked bits of wood, ironshod, each drawn by a couple of buffaloes—through what appeared to be very rich soil. We halted a few minutes at a very lovely spot, to which the town comes for 'kief' in the summer. 'Kief' means pleasure, and pleasure means doing nothing in the shade, by running water. A kavajee brings a tray of hot charcoal, on which he makes coffee, and everyone is content. A group of vast plane-trees shaded a grassy meadow, through which ran a clear and ice-cold stream which bubbled out of a cliff of gray rock that rose on one side. An ideal spot. In event of an Austrian occupation, it will be filled, no doubt, with marble tables, beer, sausages, and merry - go - rounds. Civilization has its drawbacks.

We rode on, and in a field where a whole family was at work I was amused to see a Martini laid across the baby's cradle. We were nearing a village. 'Villages' here consist of districts with houses scattered about them, often not within sight of one another. It may be two hours' ride from one end of a 'village' to the other. We passed a few cottages among the bushes, and I was told we had arrived at the Moslem village Shushitza.

We dismounted, and left the horses with the suvarris, and the Police Commissary, my travelling companion, and I went up to the nearest house. The two men sat down outside, and told me to go into the yard and see the women. These stared at me like startled deer, and then dashed into the house, calling for help to an elderly man ploughing in the field below. He picked up his rifle and hastened with an anxious face. The Police Commissary promptly hailed him, and said he was 'mik' (a friend).

The man's countenance cleared; he laughed, and came up and shook hands very heartily. We were very welcome as friends, he said. When his wife had cried that there were suvarris near he had been much alarmed, and had made sure that they had come for someone. He sat down andchattered gaily. The Police Commissary explained my errand. A lady from a distant land had come on purpose to see him. He was delighted and amused. I must see all the family. He ran into the house and called his wife and daughters. Though Moslem, they were all unveiled. He tried to make them come out and talk to us, but the sight of the police was too much for them, and they would only peer round the gate-post and laugh, so I went in to them. Drawing was impossible, as they all crowded round to examine me, and I only got one snapshot, for a dozen hands were eager to play with the camera.

They were a healthy, well-built lot, and were clad in long drawers to the ankle, and skirts, sometimes so full and short that they were like the men's fustanellas, white, sleeveless coats resembling those of the Montenegrin women, but skimpier, and orange and scarlet aprons. Plenty of silver waist-clasps and coins completed the costume. One child's chest was entirely covered with coins, cockle-shells, and odd bits of metal, and very proud she was of herself.

They examined my garments carefully, and kept bobbing out to see the police, and then popping back again. The man took it all as a great joke, and asked us to stay and have coffee, but as we had much further to go we did not accept. He said I might come and see him whenever I pleased. We said, 'T'un ngiate tjete!' ('Long life to youl') to one another, and departed. Half the male population of Shpata, so the Police Commissary said, was wanted by the police, which explained the poor man's first anxiety. Consequently, almost all the trade with the town is done by the women.Anyone who knew the language could, I believe, travel through the whole district without escort if he started with a good introduction. The laws of hospitality to a guest would often be a better protection than rifles.

The two suvarris were well mounted, and my gallant gray was eager to race them, so we went up the mountain at a surprising pace, leaving the Police Commissary and my travelling companion far behind on hired steeds. The leading suvarri, a young Christian, enlivened the route by a song, which the other answered in a high falsetto. It afforded them great satisfaction, and was a naughty song, for they firmly refused to offer it for translation later. I replied with the BrItlsh Grenadiers. After an hour or two we again sighted scattered houses and a woman or two.This was the outskirts of the Christian village of Selchan. We halted, and after a somewhat lengthy parley and some message-carrying, were told we were ' mik ' and might come on. We waited for the rest of our party, and then made for a group of houses on the crest of the hill.

Out came an old, old man, the patriarch of the place. His beak was hooky, his eyes keen, his shaven head and chin glittered with silver stubble, and though bent with age, he bore himself royally. Every stranger was his guest, he said with lofty courtesy; a meal was to be made for us at once. The fore-quarter of lamb we had brought with us was handed over to the woman to be cooked, and while the feast was preparing she came and sat with us. He had not been pleased when he first saw us, as he feared the police meant mischief; but, he added frankly, with a gleam in his old eyes, 'if you have come for anything, I have plenty of guns ready.'

He picked up the suvarri's Martini, and said his own were the same pattern. I told him that in our villages no one ever carried rifles. He was much interested.

'It is much better so,' he said. 'Yours must be a fortunate land. Here we cannot live without them. I am eighty years old. Every year all my life people have said that things will be better, but they never are. Now they are talking again about reforms. I have heard it all so often before, and I shall die without seeing peace.'

His simple dignity was very impressive. I asked his name.

'I am Suliman to the Turks,' he replied, ' but I was baptized Constantine.'

I asked if all the children had double names. The Police Commissary doubted it. They were all squatting round us, eager, healthy, bright-eyed little chaps, as keen as terriers.

'What is your name?'

'Petro.'

'And your Turkish name?'

'Regep.'

'And yours?'

'Giorgi.'

'And your Turkish name?'

'Hussein.'

And so forth. All had a double set of names, and explained they used whichever was expedient. The young suvarri, the Christian one, was very much grieved about them; they were such nice boys, and would all grow up to be shot. He spoke to them very kindly, and tried to persuade them they must go to school and learn to read, or they would all grow up ' haiduks' (brigands). They laughed. When each boy was fifteen, said the suvarri, he would be given a rifle and revolver, and taught to keep up the honour of the house. He himself had wanted to set up as a schoolmaster in Shpata, but to his great disappointment had failed, and had but recently joined the police. He had a great desire to reclaim his compatriots by civilized methods, but a school in the vernacular would be stopped, and to teach these little wild animals in Greek was almost impossible.

This was one of the worst districts for bloodfeuds, and every man in the village had blood upon him.

'But,' said both suvarris, 'they have never been taught anything better.'

Four or five were 'wanted badly,' and had been hunted for in vain. This was the reason why Constantine Suliman was the only man present, and why we had been kept waiting. The other men were probably all in hiding near. The old boy laughed when it was suggested to him, and said we were all friends to-day, and would not talk of such things. I was whiling away the time by drawing, and having my sight focussed upon a distant bush, suddenly saw a head bob up and disappear, then a second.

'The men are over there.'

The young suvarri snatched his rifle, but the Police Commissary said we were all 'mik' to-day, and stopped his search. His movement had been observed, though, for no head showed again. I learnt later that Constantine Suliman was reckoned at forty rifles.

Dinner was a great ceremony, and excellently cooked. It was served out of doors, and Constantine Buliman ate with us. We had broiled lamb, stewed fowl, a big bowl of milk, cheese, scrambled eggs, and huge loaves of maize bread.

Constantine Suliman's conversation, translated, made me grieve that I could not talk to him directly.

'We are poor ignorant people,' he said, 'and cannot travel and see the world. We thank you very much for coming to see us and us show what people from another land are like. Mountains cannot visit mountains, but men can visit men.' He regretted deeply that I could not talk his language. 'Though they tell you what I say,' he said, you will never understand what we feel about you in our hearts. You have trusted us, and you are quite safe among us.'

He pressed me to stay the night, and offered me the best of all he had. I should not have had the smallest fear of staying alone; but the gendarmes had orders not to leave me, and if we had all stayed a searchparty might have been sent from the town and trouble started. It was, therefore, impossible. I promised, however, that I would not visit Elbasan again without coming to see him. My men managed to consume the whole of the colossal meal. Constantine Suliman picked up the fowl's breast-bone to divine the future. Holding it up against the sun, he traced the shapes in it carefully.

'One of us who is here will be shot dead in a fortnight,' he said solemnly. But he could not tell which. I trust it was not himself.

When we left I asked what was the etiquette about remuneration, and was told that something might be given to the eldest woman, but that to Suliman himself such a thing must not even be hinted at. Judging by the great joy the gift gave, money was extremely scarce in Shpata. We mounted, and the old man came with us to put us on another track.

When I last saw him he was standing high on a rock, silhouetted against the sky, waving farewells to us, a noble old savage. Constantine Suliman, dignified and self-respecting, according to his lights has kept clean the honour of his house upon the mountains, and will die, unconquered, without ever seeing peace. The pity of it!

As we rode away I reflected upon the Bishop of Ochrida, a man who was supposed to be educated and civilized, and of Constantine Suliman, and his people, who had lived for eighty years cut off from all the world. Which of the two is made of the finer stuff?

We stopped at a second house on the way down. A little man in European garb rushed out; he was the schoolmaster. I was begged to wait while he fetched the school. He returned with the whole of it—two little boys and a little girl, set them in a row, and began asking them what was the Greek for 'a hand,' 'a foot,' etc. The little girl stood in the middle and answered loudly and correctly. The boys were very shy. Imagine the difficulty of taking an English village child, and having to begin by teaching it French before you can teach it to read! The young suvarri took the book from the schoolmaster and started examining the children himself. It was at once clear that he had been right in his desire to be a schoolmaster, for he got far better results from all three than did the excited teacher. These three children were all that could be mustered from thirty houses. There was a great prejudice against school. Some years ago a villager had been persuaded to let his son go to a school in one of the large towns, and the boy had returned home to die. You cannot cage falcons all at once.

Our return to Elbasan in the evening was uneventful.

My eight days there passed all too fast, paying visits and making water - colour sketches of the wonderful costumes of the neighbourhood. This was a sport that the Muttasarif entered into with great zest. Of allthings, I was to stay and see the bazar on Saturday. Meantime he walked me off to his own house, and entertained me while his wife and daughters put on their best dresses for my benefit. Then I went into the harem.

Cut off from my male interpreter, I had to make shift as best I could, for the three ladies spoke Albanian only. But the pictures in my sketch-book explained themselves, and I knew the Albanian for most of the things in it. Madame was magnificent in full native dress, and sat cross-legged in flowery bloomers, a most beautiful crimson velvet and gold jacket, and a white silk gauze shirt all gold embroidered. The whole, set off with native ornaments, was a fine rich colour scheme. Her daughters, alas ! were 'European' in long-trained skirts of pink flannel and silk blouses of bright yellow and purple plaid (Teutonic, I'll swear), trimmed with a plenty of yellow chiffon. Their hospitality was extreme.

We sat on a divan, and they put bits of orange in my mouth. Papa looked on and beamed, and when I left gave me a bunch of beautiful ostrich-feathers. He had been told, he said, that English ladies wore them on their heads. He used them for penholders. I told him he was correctly informed, and that, moreover, they were always worn at Court, which pleased him much.

On market-day, before seven in the morning, when I was but half-clad, there came a battering at my door and excited voices. The police wanted me at once. I hustled into a coat, and came on to the balcony, to find that by the Muttasarif's orders they had captured a woman of the village of Chermenik, in Shpata, for me to draw, as it was the oddest dress of the neighbourhood. She had a string of bark to sell, and was told I wanted to buy it. A crowd assembled and bargained with her for it while she raged and stamped, while I, in a most deshabille condition and stockingless, jotted her down as fast as I could lay brush to paper. She never knew she had been drawn, and we bought her stuff and let her go in about ten minutes.

I spent all the day happily in the bazar with a host of strange folk, a blaze of colour, bizarre, oldworld, decorative, all-glorious in the sunshine, andbackgrounded by the mysterious depths of hot shadow in the little wooden shops.

But all good things come to an end. The Muttasarif, kindly to the last, gave me a large bagful of oranges from his garden to eat on the way, I said good-bye regretfully, and we started early in the morning, along the Egnatian way, for Durazzo, passing through Pekin and Kavaia. Neither calls for much description, and the Roman way is almost all destroyed. According to one of the foreign Cousuls, the Turks tore it up pretty recently in a blind rage, with the intent to destroy all communications as far as possible.

The hanjee at Pekin, when I remarked that the town was small, replied promptly:

'A gold coin is small, but it is very good.'

The Albanian talks in similies very neatly—e.g., 'He went on a horse and came back on a donkey' (he failed in his errand).

The cuckoo was hollaing loudly, and I tried to collect folk-lore about it, but learnt only that the first time you hear her you should eat something, and will then have plenty all the year. The Howers we call cuckoo flowers are here 'lambs' flowers.

We spent the night at Kavaia, and left for Durazzo at five next morning. It was an easy ride, much of it along the seashore.

Durazzo is in Skodra vilayet. Roman Catholicism begins here, but out of the 1,000 houses only 120 are Homan Catholic. Books printed in Albanian by the Church press at Skodra circulate quite freely, and Turkey has no say in the matter. To show that they still possessed some authority, however, the police asked me how many letters I had sent off by the Austrian mail, and why I had been to the Austrian consulate!

I had an interesting talk with one of the priests, a dark man, keen-eyed and vehement, putting all the energy of his nature into his religion, as his forefathers would have into a vendetta, never yielding an inch of hisopinion, but accepting what was said to him with the fine courtesy that is the birthright of the Albanian and the Montenegrin. He told me the work of the Roman Catholic Church in Albania had been for a long time hampered by the lack of native priests, but Austria is now training numbers; all the Christian villages of the mountains are now supplied, and a great civilizing work is being done. I never attended service in any of the Catholic churches without being struck with the difference between the grip they have on the people, who listen in awe-struck silence to their eloquent sermons, and the slack, indifferent spirit shown in the Greek churches of the South.

Durazzo (Dyrrachium), formerly an island, is joined to the mainland by a huge marsh, partly salt, where the Government saltworks are, and partly fresh, and haunted by storks, frogs and fevers. For a Turkish port it is fairly flourishing. The Government, with unwonted energy, is making a road round the point by building a rough sea-wall, largely of smashed-up Roman remains, funeral slabs, columns and inscriptions. But Durazzo is often visited by boat, and is well known to Europeans. I will, therefore, not describe its antiquities.

I lived luxuriously at the big han, for my room had not only a bedstead, but a chair and table—the first I had met for many a long day—and a convenient cookshop over the way supplied food that tasted better than it looked. The han, like an old English one, is built round a yard, and has big balconies, in one of which lived a huge pet ram called Napoleon, with curly horns and a massive Roman nose, which the serving-men usually stopped to kiss as they passed. When it wanted a drink it baa´d loudly, and someone escorted it downstairs to the horse-trough in the yard, which was always picturesque with zaptiehs and suvarris, kirijees, and pack-beasts. The Albanians are fond of animals. I have never seen even the wildest of them torturing an animal for fun, a sight too common in South Italy.

There is a really good carriageable road to Tirana, the only one I had seen since crossing the Turkish frontier months ago. The fact that Ihad not to be perpetually balancing, steering, scrambling, and dismounting, struck me as one of the most extraordinary experlences ot my journey—as though a dream of years ago had come true. I had great difficulty in realizing that I had lived most of my life with roads as good. We went along quickly, and I saw at once by his splendid seat on horseback that the suvarri was not an Albanian. When we halted halfway he poured out a strange tale of sorrow. He was a Russian subject and a Circassian. He hated Russia with a bitter hatred, had escaped over the borders and got to Trebizond. His one desire was to go to Europe. He managed to be taken as horse-boy by a Turkish officer, and came with him to Durazzo. He then turned suvarri and married. This was two years ago. Now it had been discovered he was a Russian subject, and he must leave the force. If he became a Turkish one he must do military service, in which case he would have no pay, and his wife and child would be left alone to starve; or he must pay exemption, which was impossible. The only thing left for him was to fly in a foreign ship with them. Perhaps if he sold his horse and gun he could manage it. His great terror was that he should be given back to Russia. All he wanted was to serve the Sultan faithfully as a suvarri. Such is the curious irony of fate. The only man I met who told me he loved the Turk had to fly. To add to his trouble, his child was very ill. He looked wretchedly unhappy, and when he left, prayed me to write a note to his Bimbashi to say he had served me well. He had a forlorn hope that a certificate of character from a foreigner would help him to keep his place.

We passed a place called Shiak, near which is a group of some fifty houses, all inhabited by Moslem Albanians who left Bosnia at the time of the Austrian occupation. Ideas have changed a good deal in Albania since those days.

Tirana (12,000 inhabitants), having a good road to the port, is remarkably flourishing. A fine bazar was in full swing, crowded with country folk in costumes all different from those of Elbasan. Tirana was founded in 1600 by a rich Beg, who named it to commemorate a Turkish victory at Teheran in Persia. The present Begs, the Toptans, who claim descent from the Topias of old, and are exceedingly popular, have not only constructed the road at their own expense, but have imported agricultural implements and engaged Italiansto teach the people how to use them. One of the family is in exile for 'patriotism,' and the town laments. The land being well cultivated, the soil rich, and the road good, export trade is increasing rapidly. All the houses stand in large gardens, which are a mass of cherry, fig, quince, plum, and walnut trees, and water is laid on by a channel to most of them. It is an extraordinarily clean town, and most picturesque. The mosques are exceptionally pretty, all coloured and painted with wonderful landscapes. It is an artist's paradise, and I regretted that I could only stay three days.

To remind me, perhaps, that Tirana is in the heart of a wild land, a madman walked the streets starknaked—a big man, well fed, tall, and white-haired, with skin dark-red and leathery from the exposure of many years—who gibbered inarticulately to the sheep and donkeys. Folk seemed to stand in awe of him, and did whatever he wanted. When he insisted on walking down the street arm-in-arm with a smart officer, the effect was incomparably ludicrous.

The few Christians of Tirana are all Orthodox. The Christian schoolmistress was active and intelligent, as were all the Albanian schoolmistresses I met. Educated women are much looked up to, and very much hold their own opinions in Albania, and men seemed to be as anxious to have their daughters educated as their sons.

Even among the wild tribes, women, though the work they have to do is cruelly severe, are by no means the slaves they sometimes appear to be, but are treated with a certain rough chivalry and respected by the men. I was once with a party of men when news came in that a man in a neighbouring village had shot his wife, believing her to be unfaithful. They said indignantly this was impossible; he must have been stark-mad; the honour of Albanian women was quite untarnished; only gipsies did such things, and they lived like beasts. Each sang the praises of his wife, and explained his views on marriage with a naivete that would shock the West, though no impropriety was intended.

So great were they on women's rights, that when, in answer to questions, I told them that there were stillUniversities in England that did not grant degrees to women, they were horrified: it was, they said, unjust, unreasonable, and uncivilized.

Tirana was most kind to me. Only the Turkish Kaimmakam made it obvious that he thought my presence superfluous, and sent the police to ask me why I was always writing, and what? I had been sketching from my window.

The road to Tirana lay over the rich plain-land which belongs to the Begs of Tirana, except a piece near the coast, which the Sultan has 'obtained,' it is said, by exiling the owner. Turning towards the mountains, we saw Kruja high above us, and reached it by a steep ascent up a stony track—a six hours' ride in all.

Kruja was most friendly. Police and all were Albanian, and delighted to see me. The young, newly-appointed 'reform' judge, a Greek—the only Christian in the place—took a golden view of everything. The people were most industrious, he said. He was surprised to find them so amenable; there was much less crime than he had expected in such an outlying part. Robberies were rare, and there had been but three murders in six months in his very large district. All these people wanted was just and reasonable treatment.

Kruja was the only place that did not demand and stamp my passport. From a friend passports were not required. The police were hurt when I offered it.

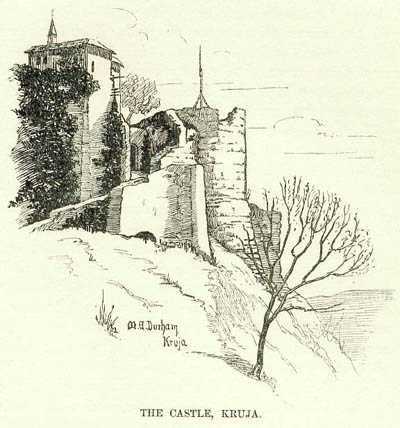

Modern Kruja consists of 700 houses, scattered up and down the slopes among olive-gardens, in the midst of which Skenderbeg's famous stronghold towers up from the mountain-side on an isolated crag. On the land side it drops precipitately to a stony valley, beyond which tower the mountains in an abrupt and rugged wall. On the sea side it slopes steeply to the plain and the Adriatic beyond.

Twice did the Turks vainly besiege this rock. The invincible Skenderbeg held it for five months against Murad II. and 40,000 men in 1450, and forced them back. Fifteen years later his successor, Mahomet II., swore to destroy the fortress, and led a yet greater force to the attack. This time the valiant Mirdites held it while Skenderbeg and his men incessantly raided the Turkish army from the surrounding rocky fastnesses. Mahomet, like Murad, was forced to retire from Kruja after losing, it is said, 30,000 men under its walls. Such is the tale of that grim rock.

A very poor, covered bazar street now leads up to the citadel, and within the walls stand only the konak, a mosque or two, three or four houses, and a tall tower. The walls are vast and solid, much of them later than Skenderbeg's time, for the crag has been defended since, both by Venetian and Turk. Some fine bronze cannon, lying on the grass, were seventy years old, and dated from the time of Sultan Mahmoud, the present Sultan's grandfather, said the Police Commissary who read the twiddly inscription for me.

High in the mountain-side above the town, in a cavern, is a Bektashite tekieh—the shrine of a very holy Dervish, Sari Salik. His body had been removed to Corfu (I give the tale as told me), and there it is revered, under the name of St. Spiridion, as a Christian saint. But, of course, said my informant, he was not really Christian.

I repeat the tale as an example of the strange mix-up of the creeds in the people s minds. The truth about saint and Dervish I have failed to discover.

Much of the population now is Sunnite, and I gathered there is some friction between them and the Bektashites. But pilgrimages are regularly made to Sari Salik's shrine, and St. George is held in very high honour. His festival was due in a week, and I was begged to stay for it, as it was the great festival of the year.

I thought you were all Moslem here?' I said.

'So we are,' was the answer, 'but, of course, we keep St. George's Day.'

But time was flying; I was already overdue in England, and, to my regret, I had to fly too.

We left Kruja very, very early. The moon hung delicately green in a sky rosy with approaching dawn, and the silver olives were magical. We left with nothing inside us but black coffee, and had been able to buy nothing overnight for the journey but some bread. The cookshop is a very lean one. A han halfway, we were assured, would supply us.

The first part of the track is as fine as any I know - huge wooded rocks and a wild stream. The sun came out hot and brilliant, and the young greenery was all aglow. Much of the way was too rough to ride. Then came a grand oak forest, where clearings had but recently been made, and men were tilling the rich fat leaf-mould. Presently the air was diabolic with brimstone, and we rode out of the trees to a clear and brilliant spring that spread and formed a little lake, reeking of sulphur that thickly coated bank and reed and stone. As a cure, the peasants value the spring highly. Hard by stands a little open shed, railed in front; within is a cross, and above a belfry. It is a Roman Catholic chapel, on a very old site, and the Christians of the neighbourhood flock to the service, which is held once a year. Otherwise it is left open and alone, protected only by its sanctity. The Albanians respect one another's holy things. In districts largely Moslem you may see a rough wooden cross standing all alone by the trackside with a little money-box attached to it.

About midday we reached the halfway han. But ´when we got there the cupboard was bare.´ Not a bite of anything did it afford. We sat under a tree, and munched our dry bread; it was yesterday's, and very, very dry. But the hanjee's black coffee put fresh energy into us.

Just as we were ready to start one of the kirijees found he had dropped his best waistcoat on the way, and must rush back to find it. He knew he had had it at the sulphur spring, and required it urgently, I believe, to go to a party in. So we waited.

To while away the time, up came a detachment of the Turkish army, some officers, and twenty-four ragged savages, three of them pure negro, one Arab, all the rest freely ' tar-brushed,' andcamped under our oak-tree. The Bimbashi, with huge white, tusky mustachios, had his blanket spread near us, squatted down with his Izbashi, and proceeded to eat a hearty lunch, remarking truthfully that 'it was better in the belly than in the bag.' It was a very good lunch, and plenty of it. He kept throwing nice little meaty bones to his dog. Such was my ravenous hunger that I should have picked them up and eaten them myself had he not been looking. But I could not steal, and to beg I was ashamed. The poor lean Tommies fared yet harder. They had nothing at all but cold water, and, like us, had been on the road since four in the morning. They and I watched the dog with common interest.

Two wild-looking youths came out of the han and squatted by us, one quite a boy, with a dull, ferocious face, the other rather older, a good-looking fellow, gray-eyed and yellow-moustached; both of them short and wiry, cartridge-belted, and armed with rifle and revolver. They were Mirdite zaptichs, they said. I asked why they were here outside their frontiers.

The better-looking one was delighted. He wrinkled up his eyes and laughed out frankly.

'We are free Mirdites,' he said joyously. 'If they did not pay us here to protect them we should come and pay ourselves. We are the men of the mountains.'

I laughed aloud. He was very pleased.

'Tell the lady,' he said, 'that in all Mirdita we only pay 100 paras of tax' (5d.=no taxes).

I hoped the Mirdites would let me visit their land. He declared I should be very welcome, but I had better go up from Skodra. Here we were but five hours from his frontiers, but the track was such that only a Mirdite could climb it. Was he regularly paid? He roared with laughter. It would be very bad for them if they did not pay him. He was the gayest young thing, and looked one straight in the face with honest eyes. I think he played the game straight as he understood it. I had three parts of a mind to ask him to take me up to Mirdita there and then, for the wilder these creatures are, the safer you are with them, if they mean to be friends. But a sudden trip to Mirdita would not have suited my companion's business.

A pack of gipsies were camped close by. The Mirdite hailed a small boy and began to chaff him. The little 'gippo,' lean, black, and monkey-like, came up cautiously. He was nine years old, he said. His brown hide showed through his ragged shirt, and he had a big pistol stuck in his sash. He snarled till his white teeth glittered, clapped his hand on his pistol, and said he could shoot us if he liked. I asked if it were really loaded, and the Mirdite was of opinion that if he were teased enough he would shoot for certain. Hand on weapon, the little wild animal swaggered off defiant.

The kirijee turned up, happy about his waistcoat, and the young Mirdite kindly set us on the right track.

All along this fat plain-land the peasants own their farms and are well-to-do. Most of them are Roman Catholics. One who hailed us owned ninety head of cattle ancl seven hundred sheep, and was accounted wealthy. Everyone in Skodra vilayet goes armed, whether Moslem or Christian. My two kirijees carried rifles, and said they never travelled that road unarmed for fear of the hill-tribes. They were Kruja men, and sang an almost endless song about Skenderbeg, which went on at intervals all day. Skenderbeg is a great hero in his own land.

We passed Debristina, the seat of a Catholic bishopric, and crossed the river Mati in a fine caik, made of two dug-out tree-trunks lashed together. We were now on the marshy flats called Bregu Matit, and could see on the hilltop over near Alessio the holy tomb of a Moslem saint. The kirijees told his story.

He lived long, long ago in the town, and was a butcher. One day a man came and bought some goat's flesh. Presently he returned and said it was not good. The butcher had none left, so killed another goat and gave him of it in exchange. Back came the man shortly, and said the flesh of this goat, too, was bad. The butcher slew another. This went on and on, and the butcher never complained or lost his patience. When he had killed his fortieth and last goat, in despair he hurled his knife into the air. Spiritsseized on the knife, and it flew away and away and dropped on the very top of the hill. Then all the people saw that the butcher was very holy. From that day forth, indeed, he seems to have been a 'made man.' He was held in great repute, and when he died was buried on the spot were the knife miraculously fell, and even now it is a very good place to which to make a pilgrimage.

As we approached Alessio I felt as if I were nearing home. The dresses of the peasants were all such as I had seen a hundred times in Skodra, and they looked like old friends. But Alessio is but a dree place, and cannot be recommended for a prolonged stay. Its han is the very leanest I know, which is saying a good deal. A man very kindly turned out of one of its wretched cock-lofts for my benefit, but it was stacked with all the belongings of himself and a friend, including their dirty clothes, had five swallows' nests on its outer wall, only holes for windows, and large slits between the floor-boards, and the cookshop had nothing in it. We had to go to the butcher's and buy a sheep's head and liver and take it to be cooked.

It was five when we reached Alessio, and we had left Kruja a little after 4 a.m. We had had nothing to eat but some dry bread all day, and when the dinner would be ready the cookshop man alone knew. I had to drink half a bottle of wine before I mustered energy to explore the town.

It is a mean little place, mostly Christian, and stands on the river Drin, which I looked at with interest, for it rises in Lake Ochrida, but it is here a shrunken, dwindled Drin. In 1858 it suddenly forced for itself a new channel, and the mass of its waters now pour into the Bojana just below Skodra, and, by blocking the current of water from the lake, causes dire floods every winter.

Beyond the river is a church and monastery. Of the old cathedral nothing remains, and the site of Skenderbeg's grave is unknown. All that remains of the Venetian occupation is the ruined citadel on the hill above. A sprinkling of houses and a wretched little bazar make up all there is of Alessio now.

A gendarme came up and hailed me in Serb:

'How is thy sister, and hast thou made many pictures this year? I know thee well. Every year dost thou come to Skodra.'

He was going with some others to try and collect taxes, but did not think they would get much.

'Ah, if thou didst but know my fatherland! I come from X .'

I knew it. He was delighted. If I had only seen his brother and his 'stara maika' (old mother)!

'Knowest thou, when the Austrians came I was a boy. People told me it would be much better with the Turks. I did not know. I was a fool. My brother stayed with our mother, and I came to the Turks. Two years ago I went back "kod nas " to see my stara maika. Now the town is very beautiful. My brother is rich; he has sheep and a fine house. Look at me!' He pointed to his ragged uniform. ' By God, I was a fool !'

It was dark before we got our sheep's liver, which was swimming in gravy in a large bowl. I shall never, never eat such a delicious one again.

At night the han was so picturesque that its deficiencies could be forgiven it. It was a great ramshackle barn, with lofty roof all rafters and cobwebs. The floor was spread with straw and hay, and the pack-mules and horses of passing traders tethered to the walls. On a raised stone platform in the middle the kirijees and peasants cooked their evening meal and passed the night. The flickering fire-light cast bogy shadows, and threw red light on their keen faces. I climbed to my dirty cock-loft, blocked the windowhole with a shutter, for the wind blew cold, heard the grind, grind of the pack-beasts munching below, and was soon asleep with my head on my saddle.

I was waked at very earliest dawn by the swallows. By putting up the shutter I had shut them all in, and they were dashing about the room, banging on the walls, and cursing loudly.

It was Holy Cross Day, and folk all carried little crosses of two sticks, tied together like the cross of the infant St. John in the old masters. The ride to Skodra is a very easy one, all along the Drin, over theplains called Zadrima. Most of the villages are Christian; some possess very old churches.

San Giovanni di Medua (in Albanian 'Sinjin'), the port for Skodra, lies on the coast but a mile or so away from Alessio. But though it is Skodra's port, and Skodra is the capital of North Albania, it has only just occurred to the authorities that it would be a good thing to make a carriageable road. 'Next year ' is to see that accomplished ! The kirijees left their rifles at Alessio, to be picked up on their return, the way being of the safest, but the authorities thought fit to send a suvarri with me. As I was used to messing about Skodra unprotected, I felt much humiliated to enter it thus.

We arrived without adventure at Bachelik, the suburb of Skodra, on the banks of the Drinazzo, and it all looked as familiar as Oxford Street. But I had never arrived at the town by that route before, and had not realized that a Custom-house examination had to take place on the bridge.

' Give me a medjidieh ' (3s. 4d.), said I to my comrade.

Alas ! he had not a penny of change, and nor had I. Change is a great difficulty when travelling in Turkey, and can only be got from professional changers.

Out came every ragged, dirty article from my saddlebags. Down squatted everyone and searched them. I had a couple of books, which I should have hidden had I known beforehand. They were harmless works, but I had reasons for not wishing them to fall into offficial hands. They were seized at once. Then came my travelling inkpot, hard, heavy, suspicious. They set it on the ground, and someone applied a finger to the spring. Up went the lid with a pop, and they jumped out of the way with a hurry that showed they feared explosives. I dipped my little finger in the ink, and approached it to the nose of the nearest man. This is the sort of joke they think really funny, and it soothed them at once. They replaced everything except the two books. I put out a hand carelessly, picked them up, and put them in. No; they were at once removed. My guide said it was no use. I must get them back later through the consulate. His goods were then examined. It took some time. My books lay on the sill of the Custom-house. Everyone spoke only Albanian. On the off-chance I cried aloud in Serb:

' Please give me my books.'

Up came an officer who who was hanging around.

' Ah, thou speakest my language ! I am Bosniak !'

He babbled of his fatherland, and examined the books. One was a French dictionary, the other an Italian work on Albania. He was troubled about them, especially the dictionary, put them down again, and I gave up all hope. To my surprise, just as I was mounting, he suddenly exclaimed:

'Here, lady ! I give thee thy books because thou speakest my language!'

I shoved them into my holsters, unspeakably relieved, and in another twenty minutes drew rein at the door of the Hotel de l'Europe. Out rushed the family, and before I had time to dismount, cried: 'Your sister sent us some Christmas cards !' and quite a number of unknown persons hailed me as an old friend.

CHAPTER XIII

MIRDITA

SKODRA again at last. I did not know if I were glad ir or sorry I had arrived. There is a certain charm about reaching a goal that has been before one for weeks. But the grip of the wilderness was upon me, and the charm of the mountains. When I saw myself in a mirror for the first time after all these glorious weeks, I was sorry for the ragged, copper-coloured thing, as 'fit as a fiddle,' that had to be caged in the West in a few weeks' time. I must see Mirdita before I tore myself away.

Skodra previously had always resolutely opposed all my schemes for seeing the interior. It declared the life was too rough. Now it was prepared to give me any amount of help.

The vilayet of Skodra is the freest of all. It gives only voluntary military service, and does not pay tobacco duty. The Turkish garrison lives for the most part in the town, ~ because,' as the Albanians will tell you, ' we do not like them to walk about the country.' For Skodra vilayet is the home of the Maljeore, the mountaineers—the true sons of the eagle.

The Turkish Government is well aware that there are limits that cannot be transgressed without bloodshed, and both parties keep the peace with loaded rifles. I did not visit the Turkish Vali here. I put myself in Albanian hands, and was introduced to the Princess of the Mirdites, mother of Prenk Bib Doda, their exiled chieftain.

The Mirdites, since the days when they are first heard of, have been famed the finest fighting men in all Albania, and of all the tribes the most independent. Old Bib Doda, with his Mirdites, fought gallantly on the British side at the Crimea.

The Turks dreaded the growing power of the tribe, and at the beginning of the war in 1876 detained at first one of the princely family as a hostage for Mirdite fidelity. Prince Prenk, then a youth, took no part in the war, but planned to strike for complete independence. It is said he was in treaty with the Montenegrins. Most unfortunately for the Mirdites, an armistice was proclaimed between Turk and Serb (1877), and the Turk having thus a very large army at liberty, turned it suddenly against the Mirdites. Till then the Mirdites had been unconquered and invincible. Modern arms and methods were too much for them. It is said also they were outnumbered. They made a valiant stand, but Dervish Pasha forced his way to the capital, Oroshi, and burnt it. The princely family escaped, but the young Prince was afterwards captured, and has ever since been an exile at Kastanundi in Asia Minor. A Turkish Governor was appointed to Mirdita, but has to live without its frontiers.

The Mirdites having lost their leader, the Turks thought it as well to leave them alone, and for twentyfive years they have lived ungoverned and leaderless. The fate of some of the other mountain tribes has been similar. Europe has treated them scurvily, and the Turk has made scapegoats of them.

The aged Princess and her daughter the Princess Davidica, received me with the greatest kindness at her house in Skodra. She wore native dress and spoke only Albanian. Dark, dignified, and with an eternal sadness in her eyes, she is a mother eagle, mourning always for her captured son, and her heart is up in the highlands with the wild men of her dead husband's tribe.

She and her daughter, whose personality is as marked as her mother's, kindly offered at once to send me up the country with their own men, and with an introduction to Monsignor the Abbot of the Mirdites. If I would only tell England about them, that was all she asked. It will be long before I forget the aged Princess, when she begged me to ask the help of England, that loves freedom for her exiled son and his friendless people.

My travelling companion had come to his journey's end at Skodra, and had only to do his business and return, and my former guide, Dutsi, was now in service, so I hired one Jin to come up with me to Oroshi, for the Princess's men spoke Albanian only. Jin was rather a dear old thing; had been kavas to both the Austrian and British consulates; had been in the habit of valeting his masters, and, with the best of intentions, strove to do the same for me. As the above-mentioned gentlemen wore garments quite other to mine, poor Jin came badly to grief when he took it upon himself to explore my saddle-bags. The result of his well-meant efforts was far too funny for publication.

With Jin and two magnificent Mirdites—one the Princess's own kavas and the other a Mirdite zaptieh— both in brave attire, I started through the back of the town and over the plain towards the river. A tall block of antique masonry near the track and a second in the distance were, so Jin said, the remains of a bridge that used to bring water from the mountains many hundred years ago. A Roman aqueduct, probably, for Skodra was a Roman station.

Soon the plain ceased abruptly. High mountains rose suddenly, and the Drin rushed from out a narrow valley. We crossed over in a caik to the village opposite, which was full of soldiers. Close by, at Mjet, is the residence of the so-called Turkish Governor of Mirdita.

Having lunched at the village han, we struck up into the mountains of the Mirdites. It is all mountainous, but quite unlike any of the other Albanian districts that I know. The soil is a light brown sandy loam with but little rock. Roads could be made here without much difficulty, as little or no blasting would be required. And the whole is thickly wooded. Mirdita, in fact, so far as I saw it, is a huge tract of forest-land, a large part valueless, except for firewood, as the young trees have been browsed by goats and ignorantly lopped, but there are thousands of pounds' worth of fine timber too, for the most part oak on the lower slopes, and pine above. But though timber can be floated down the Drin from the heart of the land, the Turkish Government, unwilling that Mirdita should earn money, stops the wood before it reaches the sea, and has forbidden the Princess to export. With all its capital locked up, development is a matter of extreme difficulty, and Mirdita is bitterly poor. The people make a little money by selling firewood, sheep's and goat's hides, fox and wolf skins, and the roots and bark of the sumach-tree (for dyeing and tanning). They buy some of their maize from the plain-land, otherwise the country is almost 'self-contained.' Everything is home-made, and all a man has to buy is his gun and ammunition. Every man is armed, usually with 'Martina' and revolver.

Oroshi can be reached in one day from Skodra, but my friends there, unaware of the iron condition into which Albania had wrought me, arranged that I should take two over it. We tracked along in leisurely fashion up the Gjadri, a small tributary of the Drin, meeting now and again a party of natives heavily laden, carrying their goods for sale at the frontier, or a herdsboy, who stared with astonished eyes. Otherwise a few scattered huts were all that told it was an inhabited land. But after the gray desolation of the other mountain tracts of Albania, its greenness and the warm colour of the soil looked almost English.

At eventide we all arrived at a nice little house on a hilltop, with a greatwooden cross alongside and a little old priest at the door—a charming old man, who spoke just enough Italian for me to understand him. He was devoted to the Princess, could not do enough for anyone sent by her, and prayed me for news of the exiled Prince and all the family. He made me sit on the couch and take my boots off at once, insisted on my putting on his slippers because they were warm, and was most anxious I should take off my leathern belt. In these lands, where a heavy belt full of cartridges and weapons is always worn, the firs thing a man does on entering a friendly house is to divest himself of the burden with a sigh of relief. Mine, on the contrary, was rather urgently required by the make of my garments. The poor old gentleman, to my horror, thought that my refusal to take it off was because it was full of money that I would not trust him with, and so distressed was he that, in sign of good faith, off it had to come. I, on the contrary, would trust all my belongings, not merely to a worthy old priest, but to any Montenegrin or Albanian tribesman, providing always that he dwells so far in the wilderness as to be uncorrupted by civilization, and has received me as his guest. Petty prigging is not one of his vices, and his boast that he never betrays a friend nor spares a foe is not an idle one.

The kindly old priest bustled about, and assured me he was treating me exactly as he should treat the King of England if he called on the way to Oroshi.

'I am giving you my best, and I could do no more for him!'

One thing puzzled him much, he said. It was very strange that the King should be called Edward when his mother's name was Victoria. He expressed great admiration for Queen Victoria, reminded me that the Mirdites had fought on our side in the Crimea, and was fiercely anti-Russian. Of all things he wanted to hear about the Japanese. A little nun came in to lay the supper, and, by the oddest chance in the world, two out of his few European plates had Japanese people upon them. He had been unaware of this, and was much interested.

England was the only nation that could be trusted to act fairly towards Albania, he said. All the others that pretended to be friendly only wanted to take it.

'Ah, la povera Albania !' he cried, ' e morta ma'—with a little smile—' non ancora sepolta.'

We had the cheeriest little supper of roast mutton, macaroni, and cheese, excellently cooked and served by the little nun, and I shared her tidy little bedroom at night.

Next morning the worthy old man took me out to see his garden, where the roses hung heavy with dew. His village, Kasinjeti, is scattered, as all the villages are, and but a house or two showed among the trees. Below us lay the densely-wooded valleys, and far away snow-clad peaks showed clean-cut and sharp through the clear pure air of the dawn—an incomparably magnificent view, all wild nature, as unmarked by man as though Adam had not yet been created; and, travelling express, it can be reached from London in seven days!

With a sparse and scattered population the task of education is one of great difficulty. The children have to come long distances over wild tracks, and the parents, whose forbears from the beginning of time have never been taught, greatly prefer to keep the children at home to mind the goats. The London School Board, however, at the beginning had to wrestle with a similar difficulty.

A newly-built school-house near the priest's dwelling, a schoolmaster, and eight or nine pupils, show that a start has been made. The children are very bright and learn quickly. Should this catch the eye of any Roman Catholic who has the missionary spirit, and does not mind roughing it, I commend to his notice these sound, healthy, intelligent European children as offering a far better field for useful work than the blacks farther from home. None but Roman Catholics should apply.

The little nun made me up a packet of food for the journey; the Princess's kavas returned to Skodra, and, having said farewell to my most kindly entertainers, I went my way with Jin and Antonio, the Mirdite zaptieh, up into the heart of the land. We crossed the Fan i ma, a tributary of the Mati, climbed a hill, descended into another valley, and reached and f'orded the Fan i vogele (Little Fani).

We had been steadily going up all day. Near the river stood the zaptieh's house, and this he begged us to visit. He and his cousin had built it, and the interior was not yet quite finished. It was a solid stone house—nothing more nor less, in fact, than a block-house constructed for defence, the ground-floor pitch-dark and windowless, intended merely as storehouse and stable, the upper floor reached by a ladder, and lighted by slits and loopholes. The floors and beams were all of oak, and very solid.

Antonio was very proud of and pleased with the house that was his castle, and hurried to do the honours of it. Such was his hospitality that he would not let me off with less than six coffees and five rakijas. He was a dark man with strongly-marked features, tall, lean, and very long-necked. The long neck seemed to me a Mirdite peculiarity. As a whole, the Mirdites, as I saw them, did not strike me as so tall as the rest of the Albanians, but they are extraordinarily supple, wiry and active, have very good brainpans and bright, keen faces. I could not decide whether dark or fair predominated.

The women wear a costume unlike any of the others that I have met—a long white shirt, tied round the waist with long red woollen fringe that forms an apron in front, and long linen trousers to the ankle elaborately embroidered with dark red. Over the shirt either a white, sleeveless coat with red patterns applique over the seams, or, instead of the coat, the short black, square-collared jacket ('djurdin') worn always by the men in other parts of North Albania, and said to be mourning for Skenderbeg. The Mirdites assured me they were Skenderbeg's own men, and that is why both men and women wear this garment.

The Mirdite women cut their hair in a straight fringe over the forehead, but plait that at the back, and tie it up in a handkerchief. They were decidedly short, but very strongly-built and deep-chested. I should think lung diseases were unknown in Mirdita.

From the zaptieh's house it is but a short way to Oroshi, and Oroshi was a great surprise. It is in the midst of what is, perhaps, one of the least-known and most isolated peoples of Europe, and it contains one of the most civilized houses in all Albania, the home of a man who is one of the strong personalities of the NearEast, Monsignor the Abbot of the Mirdites, who, single-hearted and single-handed, a man of culture and learning, has devoted himself to the saving of his wild brethren, and lives in the wilderness cut off from all the world.

The Abbot is his own engineer and his own architect. On a wide shelf on the mountain-side stand the church he has planned and built, his house, and the school. The tall white bell-tower of the church stood up white against the mountain beyond, which is cleft by a wide gully, terraced and cultivated. Some twent houses are scattered up it. This is Oroshi, the capitaI of the Mirdites. Before the inroad of Dervish Pasha it was a flourishing village of a hundred houses. Now ruins mark where many a house has stood, and the home of the Bib Dodas has never been rebuilt.

The Abbot, whose title is the traditional one for the head of the Church in Mirdita, is in reality a secular priest, for the Benedictine abbey of Oroshi was long ago destroyed. His position is quite a unique one. This wild land of 30,000 people has no temporal head. It is princeless, and there is no tribunal of any kind before which a criminal can be brought. The Abbot is the only power in the land, and his power is purely spiritual. Exiled by the Turkish Government when quite a young man, he spent the years of his exile, not as do so many Turkish subjects, in Asia Minor, but, by the aid of the Church, under British government, first in Newfoundland and afterwards at Bombay, where he used to hear confessions in English. But his heart was always with his poor Mirdites, all unhelped in the wilderness, and after long years of exile he succeeded in obtaining a hearing at Constantinople, pleaded his cause, and won it. Now for fifteen years he has toiled for his brethren, striving by prayer, preaching, an example to win them from their state of prehistoric savagery.

He has fifteen parishes under him, all of which he personally superintends. The difficulties to be struggled with are such as would crush a less able man, for it must be remembered that the land is without any form of government, and any attempt on his part to establish a tribunal to punish crime would be exceeding his duties as a churchman, and be regarded as a breach of faith with the Porte.

He has one powerful weapon to wield, and one only —that is, excommunication. Only by his own religious and moral power can he influence the people. He was extremely modest about the success of his efforts, but the respect in which he is held is marked and obvious, and the fact that his house is a quite European one, with large windows, speaks for itself in a land where every other house that is not a mere wooden hut is a loopholed block-house.

'Those that I can induce to come to church I can influence,' he said. 'With the others I have the greatest difficulty. When a crime is reported to me, all I can do is to denounce it from the altar and call upon the man to come and speak with me. He is usually not present, but the message is taken to him. Sometimes I fail entirely; sometimes he comes after many messages, and I speak to him of what he has done and what it means.'

It is almost always murder. These people are not thieves among one another, but on human life they set not the smallest value. I have been told that a man, after killing his enemy, has been known to regret having wasted a cartridge on such a paltry object. The vendettas, as in Shpata, are so numerous that most families owe somebody blood.

The fifty Mirdite zaptiehs instituted by the Turks when they 'conquered' Mirdita are, like other Turkappointed officials, rarely paid by the Government, and as there is no prison to which to take a prisoner nor anyone to try him, there is little use in arresting him. The chief use of the zaptiehs is in providing armed escort to such as require it. Every stranger not properly introduced and vouched for is looked on with suspicion, and may be shot at sight. And the people cling jealously to the right of private vengeance given them by the law of the mountain, the prehistoric code which is all they know. Few of them go even to Skodra. They live in the same way as did their ancestors in Alexander the Great's day, and, having seen nothing else, are entirely content with it.

The Abbot spoke with a sigh of the comfortable cottages ofNewfoundland, with curtains in the windows and pots of flowers. ' My poor people,' he said, 'have not the least idea what comfort is.'

Under his teaching, however, they are raising more flocks and tilling more ground. His own well-cared for flocks and fields form a good object-lesson.

He was extremely busy, for next Sunday was the feast of St. Alexander, the patron saint of Mirdita, he expected a gathering of the nation, and was to put up twenty-five priests in his own house. A gang of men was at work levelling the ground by the church and putting up a shrine. Preliminary services were being held in the church, and monsignore was wanted here, there, and everywhere. Had it not been that I was his guest, and there was nowhere else that I could stay, I should have much liked to have seen the gathering, but I could not trespass on his hospitality at such a time. Of his kindness I cannot speak too highly, and in all his rush of work he made time to tell me about his land and people.

He said, with a laugh, that when he came back from his long exile he was surprised to find how English luxuries had unfitted him for roughing it. He had had no idea before how rough the life in Albania really was. He declared that he was the only person I should ever meet who not only knew the life I had been brought up to, but the one I had been leading for the past weeks. It ought to have killed me! We laughed over the fact that, on the contrary, it had suited me passing well; as a matter of fact, by this time it was European habits that struck me as strange, and when he served me with afternoon tea and biscuits I was amazed.

I spent the next day walking about, seeing the school, and talking with its master, who spoke French. ! In the afternoon there came down two wild men to speak with monsignore, one of them quite young. All three walked up and down and up and down in deep and earnest conversation. Monsignore had a chair brought out at last and sat, and still the talk went on, and evening drew near. When at last they left, he came and told me the story. I can tell it but briefly. I can give no idea of the power of the man who told it.

The younger of the two men was an orphan. He had been brought up by an uncle, who had been a father to him and whom he loved much. Two years ago, as the uncle was returning home one evening, he was shot dead onthe track. It was a cold-blooded and brutal murder, founded on some fancied slight or dislike, and had no hereditary blood-feud as an excuse. By the law of the mountains it was the young man's duty to avenge his uncle. There was no other way of punishing the murderer; but by so doing he would start yet another blood-feud and a long train of murders. Monsignore sent for him, sympathized with him in his grief, and exhorted him not to follow up one crime with another.

After hours of prayer and persuasion he won his point. The young man gave his word to withhold his vengeance for a year. These people live in a state of 'gyak' (blood) or 'bessa' (peace). When they have g sworn bessa they never break their word. He went back home, and the murderer lived. When the year was almost ended monsignore sent for him again. He came. This time his bessa was obtained with very great difficulty.

Now, the end of the second year was coming, and monsignore had given out in church that the young man was to come to him; but this time he sent a message that he had waited long enough for his vengeance, and would not come. Monsignore sent as before, I believe, three or four times, and feared that this time he was about to fail. But no. This afternoon the youth had come, with an older friend, to explain that his mind was quite made up, and this year his uncle should be avenged.

Then had followed the long argument which I had witnessed. It had been a severe wrestle; monsignore looked worn out, but he had conquered. A third time his intense individuality, supported with all the power of his creed, had triumphed over the hereditary instinct of the mountain-man, public opinion, and the traditional law of all his race. The youth had once more given his bessa and had returned home.

'He will keep it?' I asked.

'He will keep it.'

'And is there no way in which the murderer can be punished ?'

'None.'

'And what will be the end of it ?'

'God knows. Every year that puts off the starting of more blood-feuds is so much to the good.'

The episode tells more vividly what manner of man is monsignore, than any description I can add to it.

In person he is tall and dark, and he bears his years very lightly. He is polished, courtly, and dignified. None who do not know what life means in that wilderness can realize the nobility of his selfsacrifice. He gave me his blessing when I left, and as I rode away I knew it would be many a long day before I should again meet a man who can tame the wolf of the mountains by words.

There is little left to tell. With Antonio as guard, we followed the route we had come by as far as the Fan i vogele, which we crossed and followed downstream by the track to Kolouri. This led through a more populated district. Stone block-houses with cultivated patches of ground were more frequent. In one lonely valley a woman's voice shrilled from the rocks above, a long, melancholy recitative; a rhythmic, barbaric chant in strange harmony with the landscape.

'Someone is dead,' said Jin. 'She is telling all about him and what he did.'

He hailed the nearest herdsboy. A man had been shot, he said briefly; that was all. We rode on, and the wild notes died away in the distance.

Kolouri possesses the only shop in Mirdita—a wooden shanty, whose owner serves as go-between in trade between Mirdita and Skodra, and who sells petroleum and tin-pots, the only luxuries in which Mirdita indulges. Here I passed the night and had a festive supper with Jin, Antonio, and the two shopmen.

A short ride next day brought me to the borders of Mirdita. Far below lay the plain of Alessio, and a steep descent brought us down to the village of Kalmeti and the Princess Bib Doda's country-house by midday.

Antonio was in a hurry to depart and prepare for guests at home on St. Alexander's Day. He said goodbye, and as I sat in the shade of the trees, and looked at the great mountain-wall I had just descended, I realized with a pang that Mirdita, too, was now in the past.

Time had flown. Five months had gone all too quickly. The tribes of the mountains all called me. The Shali and the Shoshi, the Klementi; there were Gusinje and Plava all to see, and they were all within my reach. But I had overstayed my time by weeks, and had little more than the clothes I stood up in. For ten wild minutes I believe I cherished the idea of buying native garments, flying back to the mountains, and ultimately borrowing my return fare from the nearest British Consul. But my route lay over the plain to Skodra, and thence via Cetinje to London.