THE BURDEN OF THE BALKANS

BY

M. EDITH DURHAM

PART II

IN THE DEBATEABLE LANDS

'Upon the Breaking and Shivering of a great State and Empire, you may be sure to have Warres. For great Empires, while they stand, doe enervate and destroy the Forces of the Natives which they have subdued . . . and when they faile also, all goes to Ruine and they become a Prey.'—BACON.

CHAPTER V

EASTWARD HO!

FROM Vienna to Semlin I suffocated in a cruelly overheated carriage. My companions, all young Magyars, played cards and quarrelled at the top of their voices, and the corridor was crammed with sheepskin-clad peasants who had overflowed from the already packed third-class. They were said to be refugees from Turkish territories who had fled from the wrath to come, and were to be dumped in the Slav-speaking districts.

One of the Magyars spoke to me in his native tongue, and was surprised that I did not know it. Another tried German upon me, and translated for the benefit of the company. 'The Freulein,' he asked, 'is learning English ?' I had an English book in my hand. 'I can read it very easily,' said I. They were astonished, for they had been told it was a very difficult language, and were still more so when I explained my nationality, which none of them had suspected. This has happened to me often before, but never without giving me a curious sense of having lost my identity, and I am always taken for something Slavonic. Now I was supposed to be a Croat: 'Naturally, for you look quite Croatian.' The Croat hates the Magyar, and the Magyar despises the Croat, so this statement amused me vastly.

They left shortly afterwards. The train rushed on through the dark. There was a blast of cold air from the corridor, a loud yell and a scramble. One of the peasants, unused to railway travelling, tried to get out of the train, and was collared only just in time by a gentleman in the next compartment.

Passports were inspected on the Hungarian frontier, and restored on leaving Semlin. I was already in the lands where everyone is 'suspect.' The train thundered over the iron bridge that joins the banks of the Save, and drew up in Belgrade. The soft Servian accent rang familiarly in my ears, West Europe faded away like a dream, and I plunged into the Near East and the whirlpool of international politics.

It was the night of December 23, 1903. A great black funeral car was drawn up in the lamplit station; black-robed ecclesiasts moved on the platforms; a mourning crowd hung about and candles twinkled. Firmilian, Bishop of Skoplje (Uskub) was dead, and his mortal remains were to be borne back for burial to the seat of that bishopric which Servia had regained after long years of struggle. Now, after less than two years' triumph, he was dead, and Servia lamented— not because he was beloved as an individual, but because he had represented a national principle and a political victory. So, as we whirled across Servia in his funeral train, my comrades spoke much of the dead, and used him as a text on which to preach Great Servia. They were all Serbs, young and aflame with patriotism.

I found that my acquaintance with the clan Vassoievich was a passport, and the name of its leader one to conjure with. Talk all ran on unredeemed Servia and King Peter, who is to realize the national ideal. 'Now we have a King who is as good as yours,' they said, 'and Servia will have her own again.' And on the whole long track folk turned out in crowds with priests, candles, and banners, and wailed funeral chants.

This began at Nish, in the black before the dawn with never a star overhead. It went on all day at station after station; wenever forgot that Firmilian was dead, and that Old Servia had yet to be redeemed. This was rubbed into us hard on the frontier—at the best of times there is something uncanny about the Turkish frontiernow—where we stayed for an hour and three quarters, and were searched for dynamite. There was no time even to offer backshish; the whole of everybody's possessions were tipped out on to the dirty ground, and we waded knee-deep in one another's worldly goods, in which the officials sought for contraband with the minute industry of monkeys after fleas. Then followed pocket-searching, punching, poking, pommelling, astrict personal examination from which I alone was exempt, and our passports were taken.

We started again, more than an hour late, in the land of the Turk—a land that was all agrin like a dog before a fight. Pickets of lean, ragged Nizams guarded all the line, and were thick by the bridges; officers and men bristled in the stations and crowded the train.

My companions lauded the skill which had twice enabled Boris Sarafov to run the gauntlet of military, passport offlcials, and gendarmes, and escape under the enemy's eyes; and this is noteworthy, for it was the only word I ever heard in favour of Boris in the land where I had expected to find him a hero.

And from every soldier-guarded station rose the harsh, penetrating Servian wail; a black-robed crowd lamented Firmilian, and burned candles for his soul's salvation among the enemy's guns. With the highlystrung and imaginative Serbs, patriotism is almost a nervous disease, and the air was full of ' electricity.'

A gunshot rang out suddenly from beyond the railway bank, there was a rush of officers down the corridor, who tumbled over our legs in their hurry to get to a window. Everyone started visibly, and said, 'It has begun!' But it had not.

We reached Skoplje hours late, and as the authorities dared not run trains after dark, had to stay the night there. The funeral procession formed up, and, with a brave show of banners and candles and golden consular kavasses, the Serbs of Skoplje received their dead Bishop with the bitter knowledge that unless Russia supported their claim this hard-won outpost might be lost to them. And they buried Firmilian on Christmas Day in the morning.

The hotel was filled to overflowing, but I found quarters with a friendly Austrian railway-man, and my kindly host and hostess were grieved for mealone in a strange land on Christmas Eve, and took me with them to a Christmas-tree party. It was a glorious tree, all glitter and twinkle, with a pink Christkind on the top. The children played at railway-trains on the floor, and their elders talked of the expected outbreak. They, as did my friends in the train, timed it for the end of March for certain. We thought neither of peace nor goodwill. A man who often drove the train to AIitrovitza vowed he would not do so much longer, and we drank to each other's long life in little glasses of cognac as if we really meant it. I had never been in a land in a state of war before, and felt as if I were acting charades. No one as yet, here or elsewhere, reckoned Japan as an all-important influence in the affairs of the Near East.

'Things are quiet just now,' they said; you can take off your breeches when you go to bed. But some months ago, oh my God ! we were ready to fly to the first consulate at a moment's notice. When the rising begins anywhere the Turks will massacre every Christian they find, and make sure they never rise again in this world. And they will begin here.' Thus the foreign Christians, and they foretold I should return home by sea. At five next morning I slopped through mud ankle deep, with a man and a lantern which only made the darkness blacker, tumbled up against a sleepy sentry, and scrambled up a slippery bank to the station, where a stout and good-natured Jew insisted on standing me a cup of salep. It is a treacly drink made of a species of orchis-root, and was, I believe, a popular drink in England before the days of tea and coffee. Beyond being wet and warm it had no attractions.

Christmas Day dawned marvellously in a blaze of gold over purple mountains, but quickly faded into gray dulness. I spent it wedged between Turkish officers, for the ladies' coupe said it was full, which was a lie, and hurt my feelings. So along a picketed line all down the Vardar River, with no friendly and amusing Gavros and Bogdans to talk to, and over the dull, dull plain till we reached Salonika uneventfully.

'To-day,' remarked the hotel porter with the air of someone imparting information—'to-day is a feast-day of the Catholics!'

Greece put in a claim but a few days later for the bishopric, Bulgaria eyed the spot enviously, but the precedent instituted was followed, andSkoplje's new Bishop is Serb.

CHAPTER VI

ROUND ABOUT RESNA

TRAVELLING in the Near East has been said by many to be difficult, dangerous, and, which is even more alarming to the Cook-reared tourist—uncomfortable. It may be so. I am not capable of judging. When I am there, the only difficulty is to tear myself loose from its enchantments and return Westwards. As for dangers or discomforts, they are all forgotten in the all-absorbing interest of its problems. Its raw, primitive ideas, which date from the world's well-springs, its passionate strivings, its disastrous failures' grip the mind; its blaze of colour, its wildly magnificent scenery hold the eye. Crowded together on one small stage, five races, each with its own wild aspirations, its insistent individuality, its rightful claims and its lawless lusts, are locked together in a life and death struggle—a struggle that never ceases, though it is only now and then that it reaches such a bloody climax that it fills the front columns of the 'Latest Intelligence' sheet. No Roman Emperor ever planned a spectacle on half such a scale.

Salonika lay blotted and smudgy in a gray drizzle, far too much accustomed to alarming rumours to worry about them till obliged. And I hastened up-country to the scene of the latest developments of the international drama.

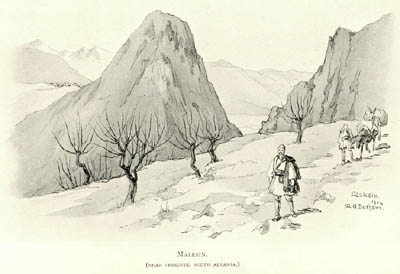

In many ways the Macedonia of Philip has not progressed in any remarkable degree since his time, but—for the Balkan Peninsula is a land of bizarre incongruities and anachronisms—it is traversed by a railway, and I travelled in the 'dames seules' with two veiled Mohammedan women, who ignored my presence entirely, moved my bag to make room for eight bundles, a cupboard, a chiming clock, and some toys, and considered that my unveiledness put me so completely beyond the pale that, to my amusement, they invited a male relative to travel with them. The train crawled slowly up among great snow-capped mountains and desolate stretches of bare rock with scrub, oak, and juniper. Philip's old capital, Edessa, stood somewhere near Vodena, which lies on the left of the line. Now, far from being the home of a conquering people, the landlay drear and abject, every station crammed with troops, and the whole line picketed by wretched Tommies, standing forlornly by their sodden tents in a condition little less pitiable than that of the refugees from the burnt villages, save that they were at liberty to loot food if any were handy. We skirted the beautiful lake of Ostrovo, and steamed into Monastir as night was falling.

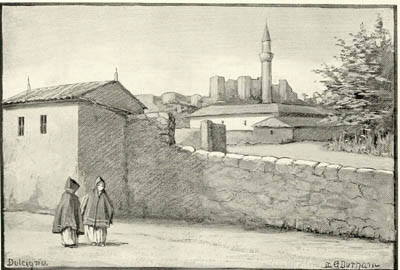

Monastir, called by the Slavs Bitolia, lies snugly against the hills on a big plain some thousand feet above sea-level. It bristles with slim, white minarets, and is boiling over with rival churches. Greek, Bulgar, Serb and Vlah build schools that are surprisingly fine and large, and the place reels with propaganda. For in a school in Turkish territory you do not merely learn the usual subjects: you are taught to which nationality you really belong, and each school is indeed a factory of 'kanonen futter,' which may some day enable the government which supports it to obtain territory. That which is able to invest most money in the business will, in all probability, come out as winner in the end.

To further complicate the already tangled knot of religions, there is a Roman Catholic mission and a Protestant one, each ready to receive all comers. Most of the Powers have consulates here. The Russian and the Austrian, as representing the two parties most interested in future developments, naturally attract much attention. Russia, ' the only Christian nation,' the beloved of the Slavs and the protector of the Bulgarian Church, is very heartily hated of the Albanian. Austria, by being affable and obliging to everybody, doubtless hopes to include the lot in Austrian territory later, and is meanwhile a popular character with all except the Slavs. But I never met anybody who believed that either had the smallest desire the 'reform' scheme should succeed, except for their own private ends.

The movements of all the Consuls, both great and small, are carefully watched; all the town knows when they call on one another, and ponders the political import of their walks abroad, and each and all spend weary hours in a vain endeavour to get questions answered by Turkish officials, a labour as endless as that of the Danaides, especially in the case of the luckless representatives of countries that have no navy nor army worth mentioning.

Monastir was perfectly quiet outwardly—that is to say, the surface of the lava was cool for the time being—and I walkedabout alone without any trouble. All trade was said to be at a standstill, and some folk were afraid to go outside the town to cultivate their fields, lest they should fall into the hands of Bulgarian bands. The streets were full of soldiers. Officers pervaded the billiard-rooms, baggage-waggons clattered firewood on the mountain with two other lads, and there came a Mohammedan Bey from Dibra with a large hunting-party. They carried off the three boys to Dibra and shut them in a cellar, and threatened to kill them all unless their friends paid £T.lOO for each of them within six months. My mother was in despair. I came home. We sold all our beasts, but with that and all my savings we had only £60. When the time was nearly gone I managed to borrow £40 from X—; he is very rich, and says he is a patriot, but he made me pay 20 per cent. for it. We bought my brother back. He was nearly dead and covered with sores. He had been in the dark all the time. My mother washed his shirt four times, and still little beasts came out of it. He swore he would be revenged some day. When the bands were made he joined. The Turks in Constantinople were very frightened about the bands. All Macedonians were ordered to leave at once. I had to go. My master said it was nonsense, and that all would be over in a few weeks, and he would take me back. Now it is four months, and still we may not return! It is my wife's fault. She is a stupid woman of my village. She has no intelligence. Many times I have begged her to live with me in Constantinople. They are stupid, like animals, these women. She and my mother were afraid to leave the village. If they had come I should not now be a Macedonian. We should be in Constantinople, and I should be having good pay. Also I should have more sons. I came home one evening. In the village was a band, and my brother was already a 'chetnik.' They permit one man in a family to take care of the women. I remained. Next day the fight began. The band was beaten. They escaped to the mountains. Then the Turks came and burnt the village to the ground. All my goats and beasts were stolen. I lost everything! even twelve new shirts I had never worn. House and all I have lost to the value of £200. We escaped to the mountains. My poor old mother suffered very much. When it grew cold we came down and found a room in another village. One night my brother comes. He says his life is not safe, and he must fly to Bulgaria. He weeps and kisses me. "Danil," he says, "I leave my wife and children to your care."Now he is safe in Sofia. He writes it is a very nice place. And here am I with three women to take care of and five children. And my sister's husband is shot, and she has three small children. But for the English flour we should all be dead. It would be better to die. How can one live in such a land? Even in peace they rob us! Last time my field was sown with maize the tax-gatherers reckoned two kilos as twelve. They took toll of us at that rate, and we had scarcely any corn left.'

A doleful tale that is typical of this wretched land.

Resna is a dirty little place of recent date. About half the inhabitants are Moslem, most Albanian, some Slav. The Christians, as usual, are split into parties. My landlady was a Vlah, a bright and rather nicelooking woman, and her husband a polyglot mongrel who, when he went to church at all, preferred the Greek variety. Madam's sympathies were emphatically Greek. Of the two churches, the Greek was the smaller and by far the older; the Bulgarian large, brand-new, and, for such a hole of a place, surprisingly gorgeous. Cakes and sweet-stuff were on sale near the door of each on feast-days.

With a desire to be strictly impartial, I attended each upon Christmas Day of the Orthodox, lighted a twopenny candle in each, and bestowed a similar sum upon the priest who begged for contributions at the door. Each treated me with kind consideration, and classed me as a male—that is, I was conducted to a spot near the front. The women in this land are usually either left outside in a sort of covered passage that frequently surrounds the church, whence they can only see and hear what is taking place through the windows, or they are shut behind a fine lattice screen at the further end of the building. There they while away the time by chattering loudly; the babies squall, and the place is thick with candle-smoke. From my exalted masculine position I observed that chattering and the sucking of sweets was the rule in our department also. And all the time the priest's long, yowling intonation rose above the general talk, the congregation crossed itself, we bowed our heads, were censed and splattered with holy water, and nobody showed the smallest reverence or devotional feeling. Nor was there anything to distinguish the ´Greek´ congregation from the ´Bulgarian.´

The attendance at one or the other is merely a case of party politics. Istared at the chattering, careless crowd and the slovenly priest as he helter-skeltered the service, and remembered, with a start at the contrast, the last Orthodox service I had attended but aix months before, upon St. Peter's Day, in the heart of the Montenegrin mountains, the rapt attention of the mountaineers, their almost painfully intense devotion, the lordly figure of the Archimandrite, and the reverence with which he read the words. My two Bulgarian comrades got a good deal more of the service than they had at all bargained for. I was too much interested to come away before the end; but as it was in the Bulgarian church that I had spent most of my time, they were quite satisfied. My land lady, meanwhile, was herded with the other women in the back part of the Greek church. A Balkan man is very well aware of his superior position. When he wishes to pay me a compliment he generally says I am as good as a man; when he has added that it is a pity I am not a gendarme or a soldier his imagination is exhausted. Some have even told me, ingeniously, that the views held by the American missionary ladies about Woman were very dangerous, and have expected me to sympathize.

Life up at Resna was rough but wholly fascinating. I lived a very 'native ' life, sharing two rooms with an Albanian and his wife, our assistants in the work, and using mine, the larger one of the two, as an office by day. It opened into a wide balcony, which was the correct place to wash in; the wind whistled through the door at night, and the pitcher in my room was a-clink with ice in the morning. Rolled in a native blanket on the floor, the cold did not trouble me, but I was bitterly aware what it meant for the destitute refugees. These often began to bang at my door and try to force an entrance as early as seven in the morning, when the chill gray dawn was breaking—unhappy wretches, clad only in rags, part of whose object in coming was to squat by my stove as soon as it was lit.

From dawn to dark I was never alone; case followed case. Now a headman and a priest to beg help for their village, now a woman with a sick child; some times a wretched old woman, blue with cold, who cried and prayed for a little bit of blanket, and occasionally a well-fed youth, who demanded a gift because he had fought in the insurrection and was dismissed with difficulty. They all spoke at once. My interpreter and the Albanian translated simultaneously into French and Servian of a sort. Those who were refused would never take ' No ' as an answer, but sat down and prepared to spend the day.

The local doctor—a little man of the Greek persuasion, who was rumoured to possess a kind of diploma —discovered the hour when I was likely to be chewing my hungry way through a lump of boiled mutton, and used the opportunity to bring in patients and strip them, that I might see for myself that suppuration had diminished, and I had one day the pleasure of seeing him dress a small sore with saliva and cigarettepaper. Resna had possessed a properly qualified man, but he was shot in the last rising, and the Greek dared not visit patients outside the town without an armed escort.

Serious cases we sent up to Ochrida, and we mitigated the lot of incurables by the gift of bedding and food in their own homes. There was in this district little illness as the results of the rising, but a number of chronic cases of many years' standing. If ever a gap of a few minutes occurred in the stream of villagers, my landlady hastened up with her mother and the baby to console my solitude, for she was a kindly soul and had a horror of being alone. She meant it so well that I rarely had the heart to object, but I confess that, when I returned one night after a hard day's ride to find ten people and five young children waiting to cheer me up, I was not so pleased as they expected.

It may appear to the reader that the obvious way to secure quiet was to lock the door. I thought so myself at first. But the only result was a sort of bombardment, in which everyone took part. The life of the peasant has deadened his intellect, blunted his feelings, blackened his morals, but he has saved himself from extinction by developing a peculiar mulish, persistent, boring obstinacy. It is a blind instinct, which can scarcely be dignified by the name of perseverance, for he applies it irrationally to every circumstance. It leads not infrequently to his undoing, but, properly directed, will doubtless play a large part in his ultimate liberation. It invariably caused me to open the door after a short resistance, but by no means always secured him the gifts he demanded.

Such was a day in the town—a drama in which most of the human passions turned up, good, bad, and indifferent, and all in the rough, with never asmear of Western varnish.

Then the villages had to be visited, and the truth of the tales sought for. There was a great charm about these expeditions. I swallowed a bowl of hot milk, having first put salt and pepper in it to hide the taste of buffaloes, and was in the saddle about eight. A chill white fog hid all the land; the roads—mere tracks pounded into deep pits—were frozen hard as iron, and need was to ride warily. I let my horse down twice before I had learnt this, but he recovered, luckily, without throwing me. We plunged across country, over hoary grass, cut off from all the world; the gendarme loomed ahead through the fog, sitting loose in his saddle, his rifle across his knees, the collar of his great-coat turned up. My man joggled behind, unhappily, for he was no horseman. We passed a heap of blackened ruins—'that was a "kafana"'; another by the stream, hung thick with great spears of ice—'that was the mill.' We rode under bare and dripping trees at the entrance of a valley, and a village showed dim in the mist.

Then came a fierce onslaught of great shaggy dogs, with bared white teeth, followed by the stoning of them and their retreat, vowing vengeance in thunderous undertones. We dismounted the gendarme, in whom I always took a great interest, for he was as yet innocent of European officers and reform, and generally an excellent fellow, sat in a shed with the horses and smoked. Then followed the house-to-house visit in company with my man, the headman of the village, and often the priest. We squished and slopped through mud or slipped on ice, according to whether it froze or thawed, climbed rickety wooden ladders to the upper floors, ducked our heads under low doorways.

I choked in the pungent wood-smoke, questioned, listened, tried in a tangle of contradictory statements to strike an average of truth; shuddered, was wrung with pity; wondered and was disgusted in turn as adversity cast a fierce searchlight on human nature, and exposed its best and its worst with pitiless impartiality. Now and then we had a joke, and I caught women taking off and hiding their silver waistclasps and ornaments, in order to look as poor as possible.

Then came the writing of the list, on which everyone clamoured to be placed. We remounted and left the village, with its sins and sorrows, for there was yet another to visit before we turned our horses homewards, and cantered back in the dusk over ground now soft, that would freeze again ere morn.

It is ill riding in the dark on such tracks, and we clattered into Resna soonafter the Turkish clock on the tower struck twelve, and told that the sun had set. My landlady flew to put wood in the stove, sprawled on her stomach before it, and blew violently into the hot ashes. There was a rush of folk who were waiting to see me, and, having dropped my man at his village, I wrestled with them single-handed. My meal was either cold or frizzled, for my landlady cooked it casually at any hour that occurred to her, and it either waited by the stove or did not, as Fate ordained. But I was so hungry that a lump of solid food was all I required. I became a mainly carnivorous animal, and after seeing the dirt of the neighbourhood never tasted water.

Asquat on the floor, I wrote lists for the morrow's flour-distribution regardless of the talk carried on all round by people who were paying a visit either to one of my assistants, my host, or myself, and their oft expressed belief that so much writing would make my head ache. My landlady, in answer to numerous inquiries, explained that I intended washing later in the water that was warming on the stove. This was a topic of never-failing interest. Then good-night, and, with the exception of a dog-fight or two under the window, peace and quiet.

But not always. One dree night I was waked, about one o'clock, by a portentous battering at the outer gate. Trusting it was in honour of some saint or other—for they had ushered in Christmas Day with similar cheeriness—I turned to go to sleep again ! No such luck. I heard scrambling below. Someone went to the door; there was a parley. Worse and worse; they were coming upstairs! I vowed that I would not receive a visitor at that hour, even if it were the Vali himself. They knocked. I took no notice. They hammered; I still lay low. They banged, thumped, thundered and shouted. It occurred to me suddenly that to feign sleep under the circumstances was absurd, and laughing, in spite of myself, I cried:

' What is it?'

' Open the door,' they cried.

In these lands everyone sleeps fully clad in all his day garments, therefore it did not occur to them that I was not in a completely presentable condition. My neglect to open the door instantly produced efforts which threatened to force it. I scrambled into an overcoat and let in an icy blast, my host, my hostess, her mother, and a man with a lantern. There was a 'telegramma' for me, they all said at once.

'To-morrow,' said I, in my limited vocabulary, for I guessed it would be in Turkish and unreadable.

'No, no,' said everyone.

It appeared that I must sign the receipt. Barefoot and frozen, I fumbled in the dark for a pencil, only to learn that it must be signed in ink. This I accomplished. Then the man proposed to translate the message, and the whole party squatted on the floor round the lantern.

After a long pause I was told that all he could understand was that it was for 'Hamham,' and had come from 'Brer.' I got rid of the whole party.

Fortunately few nights were so lively, for next morning meant boot and saddle again, and more tales of misery—hopeless, blank misery. In the burnt villages a few people were still living in the ruins under temporary 'lean-tos ' of wattle and thatch. In some cases they had rebuilt their houses. And where the stone ground-floor was only partly ruined this was not a difficult task, as the larger part of the houses in this district are built of mud and wattle on timber frames, and all the necessary material was plentiful. Ten pounds, I was told, built a good house, five, a small one; a habitable shanty was even less. But few started rebuilding, though the Government had given money for the purpose; and they seemed unwilling to help one another. Some said they would only be burnt out again, others that summer and fine weather would soon be coming. Some left the neighbourhood; the majority crowded into villages that had escaped.

If they had money—and some had—the house-owner charged them rent. If they had none, he not infrequently demanded flour of us as compensation. For one another's troubles they had, as a rule, very little sympathy. Four large families were often crowded into one cowshed, with their few goods, saved from the burning, piled around, the cattle, stabled at one end, providing a grateful warmth. I have seen a party of women warming themselves by sitting in amanure heap with their legs buried up to the knee, but people did not seem to think this an out-of-the-way thing to do.

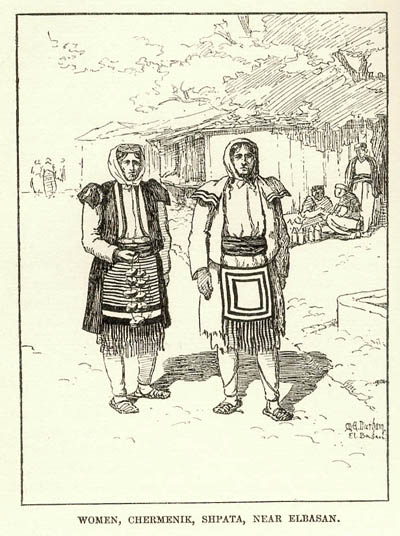

When first travelling in the Balkan Peninsula, I was struck with the fact that the natives all seemed to feel both heat and cold far more than I do. When, however, I became acquainted with the mysteries of their costume, there was no room for astonishment. I smiled when I read a pathetic tale in the papers about refugee women who had run away 'in their nightgowns.' I knew those 'nightgowns.' Saving a shirt of coarse, handwoven linen, the Christian women of these parts wear nothing at all to cover their legs but a short pair of socks. On their arms and shoulders, however, they crowd as many wadded garments as they can obtain, and they protect the lower part of the body from the chill to which it would otherwise be dangerously exposed, by girding themselves with 20 metres of goat's-hair cord, knotting it all the way up the front so that it projects hideously and forms a sort of shelf upon which the lady rests her arms.

Half the amount of clothing, evenly distributed, would keep them warm, but they pile on garments above and shiver below. I have often stood out of doors bareheaded, and with nothing on my arms but the sleeves of a flannel shirt, interviewing women clad each in a wadded waistcoat and two wadded coats and head-wraps, but I was the only one that was warm. When hot weather arrives, however, they gasp and perspire, for it rarely occurs to them to shed a garment, and anyone who possesses a fur-lined coat continues to wear it. To give them their due, I am bound to confess that, in the matter of suffering heroically for the sake of the fashion, they are quite up to the highest civilized standards.

In the winter they explain me by saying that I come from a far land where it is always cold. In the summer the highly educated talk of the well-known cold blood of the English.

Those who possessed sound garments felt the cold; those who had been burnt out in the summer, and whose clothes were now reduced to a mass of rags, suffered most bitterly, and there could be no possible doubt of their dire distress. I remember the wild gratitude of a woman, with two little children, who was absolutely destitute, as she sobbed, clung to me, and cried, ' You have saved us!'

In general, the horrors they had seen appeared to have had but slight effect upon them. The three or four intervening months had cured all nervous shock, if 'shock' there had been, for they are people of very low nervous organization. Nor, with their past history, is this to be wondered at. Once only did I find a case of 'terror' in the Resna viIlages.

A -wretched woman sitting at a cottage door, when she saw my gendarme, threw herself at my feet with a blood-curdling shriek, clung to my knees, and prayed to be saved, and then fell on the ground, stiff and only partially conscious. She had seen her husband's brains battered out, and the sight of a man in uniform always brought on an attack, I was told. But as the fit appeared to be of an epileptic nature, she was probably subject to such before. The gendarme, whose presence caused it, seemed much overpowered. He possibly knew better than any of us what manner of sights she had seen.

One has to be careful about ascribing such cases to the effects of the insurrection, however. I heard harrowing tales, which were published in some of the papers, about women who had been driven mad, and went about barking like dogs. The only one of these I had the chance of examining proved not to be insane at all, but suffering from a peculiar form of hysteria which I have met with before in other parts of the Peninsula. It is not at all uncommon among the Balkan Slavs, and also, I am told, in Russia, and the so-called 'barking' is a sort of hiccough, caused by rapid and spasmodic contractions of the diaphragm. The local remedy, often efficacious, is to direct the patient to go to church on some special saint's day, to pray for relief and to abstain from making the noise while the service is going on. If she succeeds in doing so she is generally cured. This is an interesting example of cure by suggestion.

In most cases the result of the insurrection had filled them with a dull astonishment. They said they had been told that in the late Greco-Turkish War the Turkish soldiers had behaved very well, and that they had not expected any outrages or deeds of violence. They seemed to think they might kill without exciting reprisals. With their experience of long years and the tradition of centuries this sounds incredible, but they told me sorepeatedly. Of the future they seemed to take no heed, and the past was already dulled. They lived from day to day with a sort of bovine stolidity, heavy, apathetic, interested chiefiy in petty quarrels, and seeing that they got as much 'relief' as the people next door.

In the villages that were half Mohammedan, there had, as a rule, been no fighting, and therefore little looting, and these were crowded with refugees. When visiting them, I was able to see what the unrobbed houses were like. They, of course, contain nothing at all that West Europe considers necessary for comfort, but are very much better than the mass of the huts in which the peasants of Montenegro and North Albania live. I never, even in a burnt village, had to rough it in Macedonia as I have had to do in normal circumstances in the two other lands. Here the ground is so fertile that even with the rudest cultivation it yields abundantly, and but for the heavy and irregular taxation to which the poor wretches are liable they would, as peasants go, be well off. Even as it is they make a good living, for one of the leading Bulgarians declared to me that before the outbreak there was not a beggar near Resna. The Macedonian Committee has much to answer for. Judged by Balkan standards, the housing and living was a very great deal better than I had expected after reading the published accounts. And the poor physique and bad health of the people appeared to be brought about largely by their ignorance and their habits than by want.

CHAPTER VII

ON THE SHORES OF LAKE PRESBA

MEANWHILE doleful tidings poured ill from the villages round Lake Presba—appeals for help from those yet unvisited, and rumours of small-pox. When you have once made up your mind to be Balkan you are always ready to start anywhere, at any minute. I rolled a native blanket in a waterproof sheet, put a spoon, a tin cup, a few medicines, etc., in a little bag, trusted entirely to luck that I should find food and not get wet through, and was ready for a week's travel. Every extra pound is a bother on horseback.

The Mudir decided that I must have two gendarmes, and as he had hitherto let me do just as I liked, I asked for Christians—chiefly because the Bulgars I was working with declared he would never allow it, also in orderto 'sample' the new Christian gendarmes. However, he made no difficulty, and the only Christian in the local force was allotted to me.

The start took some time. Almost every man in this land, not excepting troopers and gendarmes, rides upon a fat and squashy pillow, which he straps on his saddle. In default of this he piles up rugs or blanketing, and no one could understand my taste for the bare leather. Regularly every day the pony came round with a 'pernitza' upon it, and regularly every day I had it removed and said it was not to come tomorrow. But it always did, and they argued the point. A Montenegrin or Albanian horse-boy rarely requires telling a thing of this sort twice. It requires a week's hard labour to drive the glimmer of a new idea into a 'Macedonian.' On the sixth day the pony arrived pillowless, and I thought they had learned. But now, after three days' interval, here it was again. This time the populace was firm. A large crowd had come to see me off, and there was quite an excitement about it. I was not made of leather, they said, and the pillow was to stay where it was. They even brought a larger and fatter one. I began unbuckling the girth, and someone buckled it up again. A dozen people talked at once. According to Danil, they recounted the shocking state of their own persons when fate had deprived them of a pillow.

I learnt the great lesson that the native can be circumvented, but never reasoned with, climbed on top of the 'pernitza,' and, perched squashily, high above my beast, rode from the town. Safely outside, I got rid of the pillow, and the toughness of English hide formed a pleasing topic of conversation for many days. Danil and the gendarmes had to take care of that pillow, and long before the end of the tour said they were sorry they had insisted on its coming.

We left even the semblance of civilization that Resna possesses behind us, and made straight across country at a canter for the shores of the lake; for the gendarmes were in a sportive frame of mind, and poor Danil was left far behind. It was a casual sort of an expedition. Neither of my men knew the way after the first village or two. There are, of course, no roads, often no tracks. We followed trails of misery, picked up guides from place to place, and did not usually know in the morning where we should spend the night.

The Christian gendarme, a large and jovial Vlah, was a great invention. He had been a tradesman at Resna, had enlisted because all trade was at a standstill, and had friends and clients in almost every village. He wanted me to help everybody, and to rebuild all the churches. He was greeted with great enthusiasm, and was wildly and aggressively Christian. He kissed the priest's hand, got himself blessed and sprinkled with holy water, when there was any about, and crossed himself industriously.

His excessive Christianity and his numerous friends led to his overshooting the mark badly on 'mastic,' the local drink, the second night, and a wild and drunken sing-song raged till past midnight. Next morning, overcome with shame, he came to me and said he had behaved like a pig; that he was sorry, and while he was with me he would drink no more mastic, because when he once began he could never leave off. To my surprise, he kept this promise faithfully, in spite of very great temptation, and Danil explained that the joy of the villagers on seeing for the first time a Christian who was allowed to carry a gun was the cause of the outburst! The gentleman himself was obviously quite unaccustomed to carrying a weapon. He alternately spent much energy cleaning it and forgot all about it. On one occasion he left it behind him, to the vast amusement of his comrade, and we had to send back for it. He was a liberal-minded man, was bringing up one son as a Serb in Belgrade and the other as a Bulgarian, and his daughter was married to some other nationality, I forget which. His comrade, a Mohammedan Albanian—a long lean man deeply pitted with small-pox, which gave him an unpleasantly moth-eaten appearance—was rather 'out of it' in this Christian company. The two kept up an endless argument about the rights and wrongs of the insurrection. They never agreed, but they never lost their tempers. The Christian pointed out the awful devastation, and the Moslem earnestly defended it.

'Tell the lady,' he would say, 'that we were obliged to. They began it; they attacked us. They would kill every Turk (i.e., Moslem) in the land if they could. It is our land. We must defend ourselves.' To which Danil added: 'He does not understand. The land is really ours Naturally it is we that must kill them.'

And no one knew when the killing must begin again. The land was raw withrecent fighting—it was, so to speak, an aching wound, and either party lived in terror of the other.

We started often before it was quite light in the morning, whether it were rain, snow, or storm, and we rode till sundown. In all, we visited nineteen villages and two monasteries. I went into more than a thousand houses, and interviewed deputations from four other villages. At night we arrived, if possible, at an unburnt village, and slept and supped at the headman's house. The horses were stabled below. We climbed up a ladder into the family dwelling. A crowd of women, who called me their 'golden sister,' kissed me on both cheeks, unless I resisted violently. They spread rush mats on the mud floor. We took of our boots and squatted round the hearth, and the master of the house threw on brushwood till the fire blazed high, and I could see to write out the necessary lists. In the better houses there was a big hooded hearth of mediæval pattern; in the poorer the rafters overhead glittered black with smoke, and were festooned with dried fish, and, in houses that had escaped looting, with onions and salt meat cut into dice and threaded on string; often with bunches of plaits of hair, hung on a nail—ends to prolong ladies' pigtails on bazar days.

Then the priest in his high black cap and shaggy locks and all the chief men of the village flocked in and settled down to hard drinking and tales of the rising. Even in burnt villages where it was hard to find a meal there was always mastic. Everyone drinks from the same bottle—a quaint pewter one decorated with red glass beads. It flew from mouth to mouth, pausing every few minutes for refilling, and the company sucked the bottle and chewed leaves from a bowl of raw salt cabbage, hard and woody pickled in strong brine, or ate 'paprika,' the local pepper pod, and raised a colossal, incredible thirst. Weak mastic has little alcohol in it, but the strong variety is potent and fiery, and they tipped it down like water.

Many people came to see me, for they said, in most places, I was the only European who had stayed there except the Russian Consul. He had worked the land pretty thoroughly, and had left a tradition of fabulous wealth. The talk ran mostly on 'bands ' and 'committees.' Of their poor little victories they were very proud. When they had surprised a small body of soldiers they killed the lot, and poured petroleum on the bodies and burnt them. Then no one would ever know where they had fallen, and they could not be avenged.

' I hope they were all dead when you burnt them,' I said.

' Who knows?' they replied oracularly.

About the committees they were usually very bitter. 'They took all our money, and are safe in Sofia. We have lost all.'

Sarafov was very unpopular. The local leader, Arsov, many of them still believed in. But as a whole they dreaded the committee almost as much as they did the Turks.

I heard the same tale day after day—a hideous, squalid tale of wrong. Each village had been visited by secret agents, and the people lured by promises or forced by threats to join the movement. Each family had to pay heavy toll in cash or kind. The guns were mostly smuggled in by women, who carried them hidden in firewood or other goods. Then the rising took place—futile, disastrous, and foredoomed to failure. The wretched peasants, most of whom had rarely handled a gun, were led often by the schoolmaster, who, save that he could read and write, was but little better trained than themselves. They burned a Moslem house or two, made a plot to blow up the mosques which failed, allowed themselves to be trapped in a narrow valley; the survivors fled after a desperat struggle for life, and the troops fell on the village. Chiefty women, children, and old men remained in it and a few insurgents in hiding. There was a wild sauve qui peut when the soldiers came; a volley was fired into the thick. Some were killed, others suffered outrages at the hands of the enraged soldiery; the majority got away into the mountains, and stayed there till the cold drove them down. The women went into the villages at night to make bread from the pretty numerous stores of corn which, hidden in holes, had escaped looting. In some cases where the band had given much trouble the village was burnt to the ground, and the wrecking was so complete that all the pots and pans were piled in heaps and smashed. The church was usually plundered and desecrated. Sometimes its floor was torn up in search of hidden treasure. And the whole rising fizzled out like wet powder. It seemed, in truth, when one was on the spot, to have been planned solely with a view to bringing about a wide-spread slaughter ofthese unhappy peasants. Had there been anything like a general conflagration planned for a particular day it might have stood a chance of at any rate temporary success. But it was a long drawn out series of petty bonfires. The troops extinguished one and rode on to the next.

The Macedonian Committee's action appeared to me marvellously ill-devised. Had the Moslems chosen they could easily have annihilated every village that rose. Perhaps this was what the Committee hoped.

Round Presba, too, it seemed that the people had believed there would be no reprisals. Their total inability to learn from experience staggered me. This time all was to have been different. 'And what was to have been the end of it?' They were to have had no taxes to pay, and would be allowed to carry guns and shoot Turks. This was their only idea of liberty. Even Danil and the gendarmes were surprised to hear we paid taxes in England. Lastly, they were to be repaid the money that the 'Committee' had 'borrowed' from them. In the whole long tour through the Presba villages, to my astonishment, I did not meet one single patriot (in truth, poor wretches ! they had no 'patria'), and I found no trace of knowledge of the Great Bulgarian Empire. Out on the great lake in full view of the villages lies the tiny wooded island called Grad, and here Samuel, the last Tsar of the Bulgarian Empire, built his palace.

I asked, by way of picking up local tradition, whether anyone lived on it. No, but there must have been a monastery once, for there were ruins of a church. That was all they knew, and the ubiquitous Russian Consul had been there. Nor in Resna, among the better informed, did I find any more knowledge. Samuel and his empire were dead and forgotten, and I did not revive their story.

Danil, who was a town-made patriot of recent construction, was vexed with the villagers' apathy; but his efforts at rousing them had little effect. He tried hard to persuade them they were hardly used, because their Church service was in most cases conducted in Greek. But they bolted raw cabbage and washed it down with mastic, and only said it did not matter; many of them spoke Greek. The priest took a suck at the bottle, and was of the same opinion. He spoke the local Slav dialect himself for ordinary purposes, but he had learned all the services in Greek. It was a good service, and what did it matter? Danil was annoyed, and told me that they were very ignorant; really they were all Bulgarians,and ought to have Bulgarian priests, but they did not know. Nor, as far as I could see, did they care here. Once or twice when a man told me that he was a Serb Danil was put out, and told him he was not. A few said they were Greeks, but they all appeared 'much of a muchness.' In type they differed from the people of the Ochrida district. They were, as a whole, better looking the farther south one got. The aquiline nose and well-cut jaw that is common in Albania began to replace the broad flat face, the long upper lip, and the high cheek-bones of the folk farther north; and in the villages at the lower end of the lake the shirt worn outside became fuller and fuller in the skirt and developed into the 'fustanella' worn alike by Greek and Albanian. They confided largely in the Christian gendarme, and the local fight was fought again for his benefit.

He and the Moslem generally came in with supper. The 'sofra,' a round piece of wood on legs 3 or 4 inches high, was brought in by the women of the house, and while we washed our hands the meal was laid upon it. A bowl of broth, the fowls it was made of scarlet with paprika, often a fish from the lake, a large flat loaf of steaming hot bread, and, if the house were at all well-to-do, a 'komad.' We ate with our fingers and a wooden ladle as tools, and I was the only one who made a mess and slopped things about. 'Komad,' the local idea of a delicacy, is calculated to upset the digestion of a hippopotamus. A huge mass of pastry is whacked and thumped till all possibility of rising is knocked out of it. Then it is rolled between the hands into a long, long rope, and this is coiled round and round in a large flat dish till the dish is full. It is covered with an iron plate, shoved in the ashes, and set to bake. When it is half cooked a quantity of sugar and water is poured over it, and the baking is finished. It comes to table a sodden mass, sticky, slab, leathery, and of incredible weight.

The peasants have suffered from many misfortunes, and 'komad ' is one of them. Their diet table is, indeed, an odd one. Meat they seem to prefer heavily salted and dried into chips; some said it was the only way they ate it. Eggs they boiled stone-hard as a rule. Milk they do not care about, unless sour. Of bread, hot and heavy, they eat enough for an elephant, and of salt cabbages and onions cooked in pepper they never tire. I never saw people eat so enormously and get so little good from it. In peace times, and even after the insurrection, in the villages that had not suffered, the people have a far better food-supply, and are better housed than the mass of Montenegrin peasants, even than some of the Voyvodes.

Barring the effects of the rising indeed, I saw nowhere the dire poverty that I met in Montenegro and the vilayet of Kosovo. But the Montenegrin is fit and strong on milk and maize porridge, while the better supplied 'Macedonian' is a chronic dyspeptic, and the hardest drinker I know. Often too much accustomed to drink to get honestly drunk, he is soaked and soddened with alcohol so that he cannot do without it. Nor is this surprising, for mothers give mastic to sucking infants, and tiny children drink a heavy dose with no apparent effect.

When I asked how they had lived on the mountains, people almost always said they could not get enough mastic, and had undoubtedly felt the deprivation keenly.

After supper, mastic drinking as before, they discussed politics. No one wanted war, not even the Moslem.

' Everyone would be killed next time,' he said.

'The only thing,' said the Vlah, 'would be for a foreign country to save them. Greece had been freed by a miracle. Why not they?'

I knew nothing about the miracle, and they were astonished. The Turks, they said, outraged a little girl, and threw her body into the sea. Then God made the wind to blow, and the sea carried the corpse, uncorrupted, and threw it up on the shores of England. The people of England came down to the shore and found the dead child. Filled with horror, they went and told their King, and he sent his warships, and Greece was freed. Everyone knew the story, even the Moslem, and believed it firmly, nor could I shake them. I trust it is not equally well known on the coast, for, driven by superstition, I believe there are many who would not shrink from an attempt to summon the British navy in the same way.

They all gave me messages for the various Consuls —one about his son in prison, another about his stolen pigs, and Danil told about the twelve new shirts he had never worn. The gendarmes begged that the British Consul would apply for their pay.

The Christian, being only newly-enlisted, was but two months in arrears, and the joy of carrying a gun made up somewhat for the deficiency, but the Moslem wanted seven months' pay, and was very unhappy about it. They all discussed what would be the best thing for the Christian gendarmes to do at the next rising, and decided that they would all take their rifles and be off, which the Moslem considered a good joke. One night we talked of the Sultan. He, said the company, had murdered Abdul Aziz, and locked up his brother Murad. Murad was not mad, but was locked up because he wished to be just to the Christians. I remarked that Abdul Aziz was said to have killed himself. Moslem and all, they scouted the idea. It was well known that he had been heard shrieking for help, but the palace guards had kept the doors, and no one had been allowed to enter till there was silence. Danil vowed that his grandfather had been in Constantinople at the time, and had heard it from one of the men employed to sweep up in the palace. Another proof was that the Sultan would kill anyone; ´but naturally !' said Danil. ' So why not Abdul Aziz?'

When I had had enough of the conversation I rolled up in my blanket and went to sleep. Sometimes almost the whole party slept in the room, sometimes they didn't. It depended how many rooms there were. I believe I was generally favoured with the company of the more exalted.

To detail the tramp from house to house, the inspection of flour-bins and blankets, and the search for disease, the dull monotony of misery in every village, would weary the reader. I will mention only the more striking events of the tour.

Four villages had small-pox. In this almost unvaccinated land you have small-pox before you are five, and either die or are afterwards immune. No doctor visits these outlying parts. No precautions of any kind are taken to prevent the disease spreading, and the family shares the blanket of the patient. I had conscientious scruples about carrying infectionmyself at first, but came to the conclusion that in the general mix-up one more or less could make no difference. I found few adult cases; those were of a virulent type, semi-conscious, and with confluent pocks. The epidemic was passing over, and the surviving children were beginning to run about scarred, but recovering.

The doctor, indeed, who was sent up, on my report, to vaccinate around the infected area, said it could hardly be called an epidemic; there had not been more than thirty deaths in any place. I thought of the people at home, who are afraid to ride in a St. John's Wood omnibus if they hear of a case at Willesden, and smiled.

The small-pox chase, in fact, was not without a certain grim humour. At one village, when I was leaving, I was asked to give a little backshish to the priest's wife.

'Poor woman !' they said; 'two of her little children are ill of the small-pox, one has died, she has had it herself and is not yet well, but she cooked your supper in her own house and brought it here for you!' Another time a woman rushed out of a house, seized me in her arms, and kissed me upon either cheek until I struggled free. Her three children were down with small-pox, and this warm greeting was an appeal to me to give help.

That a certain percentage of children must always die of this disease was an accepted fact, as it was in prevaccination days in England, and the people took it stolidly. At one village there were even signs of a festivity. Hardly were we settled round the fire when a lad, very gay and smart in a red sash and a clean white fustanella, came in with a troop of friends. Shyly he offered me a glass of hot mastic.

'Take it,' said Danil; 'he is a bridegroom. You must drink his health.'

He looked about fifteen. As a matter of fact, he was just seventeen and the bride fifteen. ´They are very young,' said I, as the company chaffed him.

'It is true they are young,' said Danil philosophically. ' But it is better so, they say. Twenty children have just died of the small-pox. Maintenant on fera des autres, mais naturellement.'

And the bridegroom withdrew in a storm of jokes which Danil discreetly left untranslated.

A bride is far from holding the exalted position that she does in the West. In one house was a young woman in gaudy costume.

A silver waistclasp and strings of obsolete Austrian kreutzers, roughly silvered, gave her an air of importance. But the poor thing had to wait on everybody, women included. She kissed our hands with painful humility, and, as far as I could see, was not even allowed to sit down without permission.

'But naturally,' said Danil, 'she is the son's wife. They have only been married a few months !'

Sometimes I found traces of the old Slavonic family communities. Once a man, with the popular Servian name Milosh, gave sixty-three as the number of his family, and I found they formed the greatest part of the village. But I only found five other instances (families of from twenty to twenty-nine) in this district.

Many villages had a tale of horror. It is hard to arrive at the truth on this subject, for my experience is that these people are hopelessly inaccurate in reporting everyday affairs even when they have nothing to gain by it and do not mean to be untruthful. It is not so much a wish to deceive as a very low intelligence, which does not know what accuracy is. For instance, 'five' means a few; 'a hundred,' a great many—quite loosely. Also you may hear of the same murder in several villages from various friends of the deceased, and reckon it as four, if not careful.

I avoided leading questions as likely to suggest answers, and noted the information which dribbled out in the course of conversation. I do not guarantee numbers, but that the usual atrocities of a wild soldiery had been committed was beyond doubt. Podmacheni headed the list with forty-five killed, including twenty women outraged and disembowelled; the village partly burnt and wholly plundered, and the church wrecked. Krani came next with ten women stripped and outraged. There were four villages burnt out, and for dree misery Nakolech was the worst. Save some Moslem houses nothing was left of it, and its wretched inhabitants, squatting in mud-and-wattle huts, were living on the English flour and the fish they caught in the lake.

To add to their misfortunes a number of soldiers had been camped alongside the village since the summer, and stabled their horses in the church.

The state of the church was such that people doubted if I should be allowed to see it. An employe of the relief agency had already been refused. Some soldiers were washing clothes at the entrance. The gendarmes said I had come to see the church. I added, 'Tell them to be quick,' and after a short delay it was opened for me. It was not only littered with stable manure, but had also been recently and filthily defiled in every way, and was entirely wrecked. The wreckers had even been at the trouble of scratching out the eyes of all the saints they could reach.

The Vlah took off his cap and crossed himself boldly before a group of soldiers who crowded round the door and looked black at us. The state of the church was so disgraceful that it was beyond all words.

I think the Moslem gendarme spoke first. 'Tell the lady,' he said very eagerly, 'they were obliged to, else we should all have been killed. We must do these things to frighten them. They would kill us all and take our land.'

There was a certain feeling of thunder in the air. I withdrew as soon as I had looked well round. Outside were the commanding officer and another, who did not look pleased, but said nothing, and turned away abruptly. The gendarmes went to water the horses, and I went into the priest's hut.

Several men were waiting here to speak to me. They were terrified of the soldiers, and prayed me to have them moved. They accused them of no violence, but said they stole the washing put out to dry, and so the few poor garments saved from the burning were lost. (Here Danil told about his twelve shirts.) What they dreaded was that some day they would all be massacred. The state of the church was bad enough to report, but no one could tell me the name of either officer or regiment.

However, I learnt it later, and the Russian consulate took up the affair. I believe the officer was transferred.

The churches had suffered heavily, and it appeared that the Moslemgendarme's idea about the moral effect of church-wrecking was correct. The people were deeply affected by it. Until the churches were repaired and consecrated all religion was at a standstill. It was impossible to pray.

I asked if they could not hold a service in a room.

The priest was astonished.

It was perfectly impossible, he said. Without the proper apparatus nothing could be done.

Christianity here consisted entirely, apparently, in the ceremonial performed by the priest and a hatred of Mohammedanism.

I do not think I ever saw the picture of a saint in any of these houses. The ikon and lamp so conspicuous in the houses of the Serbs, the Montenegrins, and the Orthodox Albanians, was wanting. Nor did the people invoke Christ or the saints, or cross themselves at meal-times or before going to rest for the night. They seemed to possess none of the religious fervour that usually is so marked a characteristic of Orthodox peasants. They had more faith, apparently, in the amulets they wore than in anything else. Some of these were very odd. One was a green glass heart, two pink beads, and an English sixpence.

At German, named after St. German, one of the first missionary priests to the Slavs, we came across the one cheery episode of that nine days' tour. The village is a 'chiftlik' belonging to the Sultan's mother.

It had been but partially looted, and the church had not suffered. A festival was in full swing in honour, Danil said, 'of St. John, who did things with water.' Gay in their best clothes, the people came in procession from church, the women carrying sheaves of straw prettily plaited, and we followed up the valley. The Moslem thought he would not come, but the Vlah made him.

It was freezing hard, and a white fog spoilt the quaint scene. The priest, robed all in blue and gold, blessed the little stream which ran black between its frosted banks. He threw in a crucifix; there was a great scramble of men and boys to be first at the stream; the women dipped in their sheaves, and everyone crossed themselves three times with the holywater. The Vlah made all the responses in a loud voice, rushed wildly for the water, and came back very wet with his fez full of it for me. I made the proper signs, to the delight of the company, and he threw the rest over his Moslem comrade, who took it calmly.

Shortly after my return to Resna I read an English newspaper article, in which an impassioned young journalist described the crushed condition of the Christian gendarmes, who, he said, were made to black the boots of their Moslem confreres. I don't think I ever saw any gendarmerie boots that had been blacked by anybody, and the Christian gendarmes I had were all very cheerful; but things look so different when seen from newspaper offices.

The priest filled a caldron, and we processed back to the village. Here, I was told, he would like to bless me. I said I should be very pleased, but nothing happened. Then, it appeared, he could not bless me till he knew my name and that of my father. I supplied them; he murmured a few words; he dabbed holy water on my face with a bunch of dried, sweet basil (the holy 'vasilikon '), signed me with the cross, gave me the crucifix to kiss, I dropped a coin in the waterpot, and the ceremony was complete. When we rode away the Vlah carried a bunch of the holy basil stuck triumphantly in the muzzle of his gun.

At Rambi the usual state of affairs was reversed. It was a mixed village, and the Moslem half, with the exception of the mosque, had been looted and burnt by the Christians. The Moslems had retorted later by looting the Christians pretty completely, but I was told of no outrages. The place appeared to have been a very well-to-do one. It was once the local seat of Government. The headman's house was a really good one, and he valued his losses at £T1,000. They included two gold-coin necklaces. In this house was a mysterious Albanian in a cartridge-belt, who was very polite to me and made me coffee. I asked about him in private.

'He is a good Turk,' I was told. 'The owner of the house pays him to live here, and gives him all his food. He protects the house from being burnt. But all his friends come to feed here, too; and now the master has hardly any money left, and does not know what to do. If he tells the good Turk to go, the house may be burnt down next day.'

When I left, three friends—smart young fellows, with guns and sporting dogs—were occupying the best room. We met many such on our journey. Then the Christians said: 'To-day we dare not gather firewood; the Turks are out on a hunting-party. They would shoot us, and say it was an accident.' But I heard of no such thing taking place.

On the shores of the lake I was promised a wonderful sight; it was the one great sight of the neighbourhood —the hoof-prints of Marko's horse! Did I know about Marko? He was once a great King, and he rode upon a winged horse. Marko Kraljevich, the brave and greatly-admired hero of the Servian ballads, who was the last Serb ruler of this district (fourteenth century), was not forgotten. Christian and Moslem alike knew of his exploits. It was a fine wild scene—fit background for a mediæval warrior on a winged steed - and the fact that the marks bore no resemblance to hoof-prints was of no moment, for Sharatz was a magic horse.

We scrambled by a stony mountain-track to Nivitza, a wretched little fishing village on the other side of the lake. The people here had fled to the island of Grad during the insurrection, so had escaped; but the village had been robbed, their fishing-tackle destroyed, they had an outbreak of small-pox, and were in great distress. It was a miserable hole of a place, but possessed a large new church that was surprisingly fine. This had been robbed of its silver candles and altar-plate, but was otherwise intact. One day, said the people enthusiastically, that great and good man the Russian Consul had come here with some friends to shoot birds. He had stayed a week, paid them lavishly, and had asked if they would like to have a church of their own. Here was the church. He must undoubtedly have been immensely rich.

They begged me to visit the island and see the ruined churches on it. The priest promised to go with me next morning, and I arranged to cross the lake and send the horses round. Unluckily it blew hard when the time came, and the lake was fringed with breakers. It did not look very terrible, but the caiks were cranky affairs, and no one, even for a bribe, dared put to sea. I was very much disappointed, and had, reluctantly, to return the way I came, meaning, when I had finished my list of villages, toreturn at once from Resna to explore the island. But the gods thought otherwise.

Children in the villages told curious tales. They played at insurrections, and, oddly enough, the parents found it amusing. At one place a tiny boy of four came straight up to the gendarmes and asked for a 'fisik' (cartridge). This he solemnly wedged into the handle of the tongs, and, at the word of command, went down on one knee and brought his weapon smartly to his shoulder.

'Oganj bit' !' ('Fire !') cried his grandfather, and the child dropped flat behind a cushion and aimed at us over the top.

Arsov, the local leader, had taught him this trick, and he repeated it over and over again to the admiration of the company. Even after we had ceased talking to him he wandered round the room uncannily, and continued to cover us with his weapon from different points of vantage till the gendarme restored the 'fisik ' to his belt.

Poor little 'oganj bit' '! his father had been shot, his mother was quite destitute. I almost volunteered to take him home with me. But in the next village was a little girl who called me 'auntie' straight off and went to sleep in my lap, and I nearly took her too. Danil was delighted with her, and translated all her chatter.

The Turks, she said, were very naughty people, and had stolen her new red stockings and the little shirt her mother had made her. Now she had to wear odd stockings, and was very cross about it. If the Turks came again she should hit them very hard.

They had burned down her house, and her father had gone to build it up again, but she would stay where she was, lest the Turks should steal her new earrings, of which she was very proud.

I was asked to adopt any number of children. I might teach them any religion I pleased if I would only take them to a land where there were no Turks, and give them enough to eat. Some of these unfortunate little things, I am glad to say, have found a home and excellent training in the orphanage started for the purpose at Salonika by the Rev. E. Haskell.

The whole tour was pretty gruesome, and Pretor, the last place on mylist, was one of the most miserable. It was a little hole of a place, and all plundered. Even the best house had no glass windows, holes in the floor and a huge hole in the roof for chimney.

The master of the house, a broken old man, pointed to a spot near the door. This was where his wife was shot; the blood ran down there by the steps; she died almost at once. Then they had to fly for their lives, and had no time to bury her. When, after three months, they returned, he collected her bones and buried them, but someone, he regretfully added, had broken them. He made no complaint; he simply related the occurrence, and asked that I should be told. Here everyone was in great terror. Tax-collecting had begun. The burnt villages were exempt from taxation, but to make up for the expenses caused by the rising, the taxes were raised everywhere else—the cow tax to 10 piastres per cow per annum, and the pig tax to 122 (two shillings and sixpence), for only the Christians keep pigs. 'Ici,' as poor Danil said, though it was not quite what he meant—'ici, seulement les cochons sont Chretiens.' There is a certain grim humour, too, about taking two shillings and tenpence per head road tax in villages which have no road anywhere near them. Plundered of nearly all their belongings, the poor wretches had been unable to pay the rates they were assessed at, and were in terror lest the gendarmes should return for it. One woman, who came in sobbing, said she had offered her children to the tax-gatherers, for they were all she possessed. Another, old and blind, said the soldiers had taken all her oats in the autumn for their horses, and now she was to pay tax for them.

When night came I found that no one in the village dared sleep with my two guardian angels, so there was nothing for it but to have them myself. This had happened once before. They were very civil, and came and wrapped my feet up tenderly when they thought I was asleep. But the Vlah snored like a thunderstorm, and the Moslem got up and made coffee when ever it occurred to him. So it was about as peaceable as sleeping in a kennel of hounds. When at last I slept, I was wakened by a gentle patting, and there was the Moslem with a cup of coffee he had made for me. It was 3.30 a.m.! I growled and went to sleep again, but the kind creature made me another at five. They were both wide awake, so it was useless to try to sleep. We piled on fuel, and they smoked by the fire. It was freezing hard, and we could see the stars brilliant through the big chimney-hole. They said they feared I had slept badly, but that one soon got used to this sort of thing, and with a month in barracks and a Martini, I should make an excellent gendarme. Then by the firelight, Danil interpreting, the Moslemsaid he had something to tell me.

He had a great friend, a Mohammedan Albanian, who came from his own town (a place, by the way, that has a wild, bad reputation for brigandage). This friend had lived for years near Resna. When the rising took place he said he had always been friends with the Christians, and would not desert them. He joined Arsov's band, fought gallantly, and did much message-carrying, and, being a Moslem, was not suspected by the authorities. Finally, he escaped over the borders with the band. The Government learnt of his doings, captured his three small children, and threatened to cut their throats if he did not appear by a given date. He thereupon returned and gave himself up. He was sent into Asia as an exile, and all his property was confiscated. Now, his wife and children were in hiding near Resna, were entirely dependent on charity, and in dire want. Would I help them?

It was true they were Moslems, but they had acted like Christians, said the gendarme naively. He was very eager. We talked it all round till the clammy gray dawn crept through the holes in the walls, and having breakfasted on bread and raw mastic, we rode back to Resna through a bitter, icy wind without my having made any promises. I was pretty dirty when I got there, as I had not had my clothes off for eight days, but I learned I was wanted almost at once at Ochrida, and there was such a lot to do that I had to leave such details till the evening.

Resna entirely corroborated the gendarme's tale, and wished help to be given. I asked to see the woman and children, but was told it was impossible; my visit would arouse suspicion. The gendarme came next day, bringing a ragged little boy with him as a specimen. I asked for the woman's name. He told me, but prayed me not to put it in our list, because, as he ingenuously said, the police might find her out. None of our Christian employes had the least fear that the goods would go astray, so the conveying of them was finally left to the Moslem gendarme, who fetched them in the evening, in order that the Government, of which he was a fanatical supporter, might not find out.

I was asked by the Christians to help this case. Just afterwards I had avery different appeal. Would I knock two names off the list ? They had been put on before I came, and had drawn rations once, but they were spies, and must not have any more. They had been in Arsov's band, and had gone with him to bury the guns before leaving for Bulgaria. They left with the band at night, but doubled back in the dark, and were seen next day leaving the town with the Mudir and some troopers. A hundred and fifteen rifles was the result of the ride. Arsov sent a message that they had deserted, and he suspected them, but the deed was already done.

'I wonder,' said the man who had come to take my place—'I wonder that they are alive !'

'Monsieur,' said Danil earnestly, 'there is no one here now that can do it. But later, I swear to you, it will be done. Mais naturellement.'

I had been over a month in the district, and was sorry to leave Resna and all the people I was interested in, and especially sorry to give up the visit to the island of Grad, but I was needed urgently, and left for Ochrida next day.

CHAPTER VIII

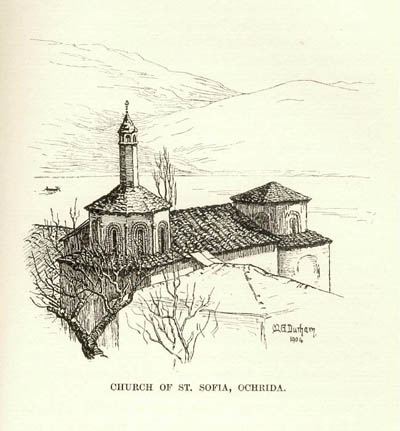

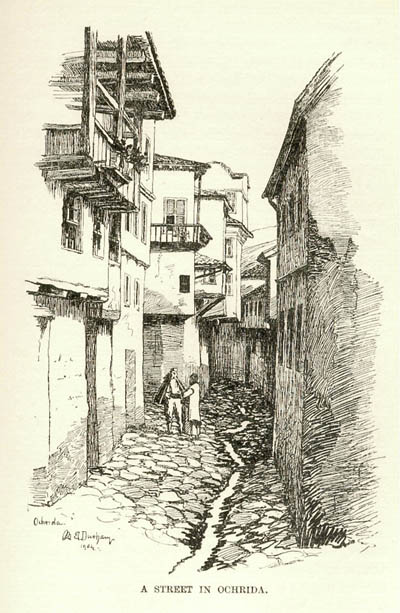

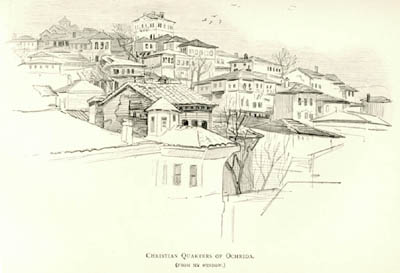

OCHRIDA

"Tis all a Chequer-board of Nights and Days

Where Destiny with Men for Pieces plays:

Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays.'

OCHRIDA hangs on a hillside, and trails along the shores of a lake that half Europe would flock to see were it not in this distressful country—a lake of surpassing beauty, second to none for wild splendour. The purple-and-silver glory of its snow-capped mountains fades into a mauve haze beyond the dazzle of its crystal waters. Its awful magnificence grips the imagination, and, in mad moments, awakes a thrill of sympathy for the unknown men who painfully hewed out tiny chapels in its flanking cliffs, and lived and died alone above its magic waters. There were times when I should not have been surprised to hear the white Vila of the ballads shriek from the mountains; and the tale of the two brothers, as told by the boatman, explained the structure of the rocks better than geology.

Upon that mountain-side there lived a man many years ago—who knows how long. He was very rich. He had many hundreds of sheep; some saythousands. When he died he left them to be divided between his two sons. But the elder was a very wicked man. He took all the finest sheep, and gave only a few that were weakly to the younger. Then God was angry with the elder brother, and struck his flock with barrenness; but the ewes of the younger all bore twins. Soon the flock of the elder was the smaller of the two. In great wrath he sent for his brother, and demanded to exchange flocks, and the younger refused. Then they fought on the point of that great rock which you see above you. They fought all day until they were both killed, and their blood ran down the cliff into the lake, and the rocks are red to this day, as any man can see.

'If there were only another Government here, how beautiful this lake might be !' sighed my comrade. 'We might have a steamboat with coloured lights and a band!'

One should even give the Devil his due; there is one point, and one only, for which I am grateful to the Sultan: so long as he reigns there will never be a road by which a trip tourist can get up-country, nor a hotel in which he can stay and play 'Arry.