THE BURDEN OF THE BALKANS

BY

M. EDITH DURHAM

PART III

IN THE LAND OF THE EAGLE

CHAPTER IX

OF THE ALBANIAN

'OH, I know all about the Albanians,' cried a lady; 'they are those funny people with pink eyes and white hair.'

But the Albanian is not so quickly explainable; and of all the Balkan peoples he is least known to the English.

His European name, ' Albanian ' is said to be connected with the word ' Alp.' He calls himself ' Shkyipetar,' and his land ' Shkyiperia '—that is, ' son of an eagle,' and ' land of the eagle '; nor could a more fitting name be found for the untamed mountain man, with his keen eyes, aquiline nose, and proud bearing.

There are two marked Albanian types, the dark and the fair. The fair is commoner, so far as I have seen, in the South. The characteristic man has a nose like Dante's, with a drooping tip, narrow in the bridge and fine cut; very marked eyebrows that start straight and drop in a slant below the orbit bone; a long jawbone that sweeps down in a fine line and ends in a firm chin cleft at the tip. The skull is straight-backed, as though a piece has been chopped off, and there is great width just above the ears, this especially in the fair type, which has brown, sometimes almost flaxen, hair and gray eyes. In figure he is tall (not so tall as the Montenegrin), lightly built, slim-hipped, and as supple as a panther. The dark type, which near Ipek and Gusinje is very dark, is often longer skulled, rather shorter in height. The tribal system and lack of communication has accentuated local differences.

Albania is divided by the river Skumbi into two parts—Ghegaria, or North Albania, and Toskeria, or South. In the South there is a considerable population also of Greeks and Vlahs, with both of which the Albanians have intermarried. North of the Skumbi, with the exception of some foreign traders and Turkish soldiers and officials, the population is entirely Albanian.

In the debateable vilayet of Kosovo there is still a considerable Servian population, but it is largely outnumbered.

Among the Ghegs the tribal system still flourishes in the mountain districts. A man when asked his name says he is So-and-so, of the Eotti or Shala. No outside man, I am told, can become a member of a tribe, and the tribe has power to decide whether a man may sell all his property away from it. He may, and often does, marry a wife from another tribe. The marriage of cousins is forbidden.

The largest tribe is that of the Mirdites, said to number 30,000. Dibra is also a large tribe. Then come the Dukagini, the Pulati (including Shala and Shoshi), the Matija, the Kastrati, the Hotti, the Klementi and the Skreli, which average 10,000 apiece, and there are a number of minor tribes of from 1,000 to 5,000 strong. (The figures are only approximate.) These tribes contain both Moslems and Roman Catholics, have their own leaders, and are not liable for conscription in the Turkish army.

In Toskeria, though certain Begs can command an armed following, the tribal system is practically dead; but the people still fall into three main divisions: the Tosks, between the Skumbi and the Viosa; the Liabs, south of the Tosks; and the Chiams, further south still. All these have minor divisions.

The language also is divided into two main dialects, Tosk and Gheg, and the difference in accent is marked. A man from Korche in the South finds Skodra talk as difficult to follow as a Cockney does broad Yorkshire. The Mirdites claim that their dialect is the purest of all, and their isolation from the world makes this highly probable. All the place-names in and around Mirdita are pure Shkyip, which points to the fact that no foreigner has ever occupied it.

Shkyip is an Aryan tongue, and has as marked an individuality as the men who speak it. Much of its vocabulary resembles early Greek and Latin; but the words often appear to be allied to, and not derived from, those tongues. It possesses, also, many odd consonantcombinations peculiar to itself. Unlike any other European tongue, it has a definite and an indefinite form of declension for nouns. The adjective follows the indefinite form, and is placed after the noun, and between noun and adjective comes what the grammar calls a 'characteristic'—a kind of article which agrees in gender with the noun and has a declension of its own. Thus: ' diale i mire,' a good boy; ' diali i mire,' the good boy. The comparison of adjectives is formed, not by inflection, but merelyby prefixing ' more ' (' ma ') or ' very' (' shum').

The verbs are capable of expressing very subtle shades of meaning, and have, according to the latest grammar, no less than eleven moods and fifty-five cases. Many of these, however, are compounds with ' to have' or ' to be.'

No written line exists to show how the tongue grew or changed. Its past is wrapped in darkness. Long historical ballads have been passed from memory to memory. Literature, save of to-day, there is none. A uniform method of writing has not yet been adopted, and Albanian is awaiting an author to crystallize it. There is a tradition of an old Albanian alphabet both at Elbasan and at Skodra, but no successful attempt to find an alphabet in which the language could be printed was made till 1879. A special alphabet was then arbitrarily constructed, a sadly mongrel affair compounded of Greek, Latin, and Cyrillic characters and some specially invented letters. With modifications it is still used by the press at Sofia, which publishes the Drita, a paper in the Tosk dialect, and various books; also by the British and Foreign Bible Society for the translation of the Gospels. But it is hopelessly unpractical and very expensive, requiring special type and type-setter, and will soon be superseded. Many attempts have been made to use the Latin alphabet, and the extremely practical system invented by Mgr. Premi Dochi, the Abbot of the Mirdites, has overcome most of the difficulties, and, owing to its great simplicity, is making rapid way.

The first book in the alphabet of 1879 was published at Constantinople, but the printing of the language was not long after forbidden on Turkish soil. The Sultan had learnt from experience that schools are centres of revolution, and would hear of no more national educational movements. Latterly he has made very active efforts to suppress the tongue altogether. In the South many people have beenimprisoned for possessing books or papers printed in it, and all schools teaching it are forbidden. But North Albania is a circumstance over which the Sultan has little control; it possesses a printing press and several schools.

A language may die a natural death. I doubt if one has ever been killed. Persecution has perhaps supplied the necessary fillip. The knowledge of reading and writing the language is spreading rapidly. You find it in very unexpected quarters, and as a common bond of sympathy it is knitting together all classes of the people. Papers printed in London, in Rome, in Sofia, and Bukarest are smuggled in and read by Moslem and Christian alike all over the land. A literary language shows signs of developing.

In Albania, even the prosaic work of dictionarymaking is spiced with a dash of romance and adventure. The story of Kristoforidh is told throughout the land with bitter indignation. A native of Elbasan, a patriot and enthusiast, he devoted some forty years of his life to the building of a monumental dictionary, collecting not only the main dialects, but visiting village after village in search of local words. He died in 1892, and bequeathed to his son the manuscript, which is reported to have contained no less than forty thousand words. The Greek Consul at Durazzo offered young Kristoforidh several thousand francs for the manuscript, and represented that his Government wished to publish it. The Greek offer was accepted; the Consul received the manuscript. Far from paying for it, he denounced the young man to the Turks for national propaganda, and he was imprisoned : for two years. The fate of the dictionary is unknown. A rumour was spread that the Greeks had destroyed it. Some believe it exists and will yet see light.

The language is but part of the national question. The whole country wishes for independence. This it cannot obtain without the consent of the Powers. A successful revolt, many fear, might lead to European intervention, and to a further extension of Slav territory. The Albanians have no rich relationsto support them as have the Bulgars, but as an extension of Russian influence is adverse to Austria, Austria is playing on the Albanian side. When Russia put a Consul into Mitrovitza in Slav interests, Austria hurried, not only to plant a rival Consul, but an Albanian school. So far Austria has 'come out top' in this district, and has neatly planted her gendarmerie officers there.

Italy, meanwhile, who would like to control both sides of the Adriatic, works hard to prove to the Albanian 'Codlin's your friend, not Short.' The astute Albanian listens to either charmer, accepts the money of both, and weighs the pros and cons.

So far as I learnt, what Albania really wants is independence, recognised by Europe, and a Prince, preferably a European one, approved of by the Powers. I met few in favour of creating an Albanian royal family, nor did I hear any of the so-called Albanian claimants to that position spoken of as having any following in the country. They are mostly outsiders, unacquainted with the land. People of all classes throughout the land hastened to explain their hopes and fears for their fatherland, and to pray for English recognition of its existence. My presence in some towns caused a most painful amount of hope. People hailed me as a saviour, and treated me as though I were a knight-errant come to redress their wrongs. I was quite unprepared for this, and it appalled me. I remember nothing more extraordinary than some of these interviews in the heart of the country, when I heard freedom preached passionately by keen-faced men with burning eyes, urgent, insistent, who prayed me almost with tears to lay their case before the British Government, saying, 'England is a just country, and she will listen to the truth.' Nor shall I easily forget the day when I was taken in at a back-door after a long roundabout walk, and heard an address in French. It was torn into pieces as soon as read, for it bore many signatures, hut I wrote it from memory very shortly afterwards:

'HONOURED LADY,

'We cannot express to you the joy that your journey gives us. We know very well the terrible sufferings you must have undergone upon the road. They must be for some good purpose. We believe that God has sent you to save us. Only in your country in all the world does true freedom exist. You have seen the misery of our land! Between the Moslem Begs, who are permitted to extort money from us, and theGovernment, which takes our money and gives us nothing in return, the majority of us are reduced to dire poverty. There are many who have scarcely a shirt to cover them. After a bad harvest many die of cold and hunger on the mountains. The people of our villages are ignorant savages, and there is none to help them. We pray you in God's name to write all day and all night, to print our misery in every paper and to ask for justice. The Slavs have Russia to help them. We have no one. We entreat you to continue the journey that you have begun. For you there will be no danger, and you will be preserved through all difficulties. We thank you from our hearts. May God save you !'

It reads coldly in black and white. Set in the aching desolation of the land it was an exceeding bitter cry— poignant, tragic, helpless, and it is but one example out of many. I protested in vain I had neither power nor influence.

Nor did folk waste time over revolutionary rhetoric. They lucidly unfolded the situation. 'Russia's interest in and work for the Bulgarians,' they said, 'has been, and is, purely for her own purposes. This England has long known. Russia is her foe and ours. Together we fought her in the Crimea. The recent risings in Macedonia are the result of long years of Russian intrigue. That land is ours. It was ours before any Bulgar set foot in it. Now they work to persuade Europe that it is theirs. Bulgaria, as all the world knows, is a poor country. Financed by Russia, these people strive to take our land. We could easily have killed them all had we wished. Europe calls them patriots when they kill us, and condemns us if we avenge ourselves. England has just given money to feed these people. We do not wish these peasants to starve, for they are the victims of political intrigue, and are very ignorant. But if England means by giving this help that she will aid Pan-Slavonic plots and help Russia to take our land, then we think it shows great ignorance of the issues at stake and great injustice. If England will give us as much support as she has given the Bulgars, we will rise as soon as Lord Lansdowne is ready, and will make a far better joh of it than they have.'

Should independence under a European Prince be denied them, they must accept the protection either of Italy or Austria. They then choose Austria unhesitatingly. In common with all the Balkan people, they believe the Austrian Empire will not last long. Austria will provide them with roads and railways, and then a break up and leave them free and provided with modern improvements. Austria has promised to allow liberty of language, and has permitted an Albanian school at Borgo Erizzo, in Dalmatia.

Italy, on the contrary, strives hard to Italianize the large Albanian colonies in Calabria and Sicily (who belong, by the way, mainly to the Uniate Church), and, having once got a footing on the further side of the Adriatic, would never voluntarily withdraw, but would pour in Italians and suppress the Albanian tongue. An anti-Italian propaganda is being worked evidently, for I was told by some villagers that union with Italy would be fraught with great danger. 'Italy possesses the holiest thing in the world—the picture of the Blessed Virgin which the angels carried over the sea from Skodra and saved from the Turks. Yet Italy has behaved impiously, and has insulted the a Pope, and the curse of God is upon her. Her people are starving, and her lands are desolate. Naturally we do not wish to fall under this curse.' Also Italy has married Montenegro, and is regarded as Pan-Slavonic.

As for Greece, her name in the places I visited produced only a torrent of abuse. It must be independence or Austria. South Albania, having suffered far more from Turkish rule than the North, seemed more ready to accept Austria. The North preferred in dependence, but might take Austria for want of better.

The Dibra tigers, as their fellow-countrymen even call them, are all for independence. Austria is reported to be striving to tame their ferocity with gold. I believe the whole country desires release from the Sultan's Government, and that they will press for it ere long.

Oddly enough, Albania's hereditary foe, Montenegro, is inclined to support her claim for independence. The wheels within wheels of Balkan politics are almost endless. An Austrian occupation of Albania would be something like a deathblow to Servian national hopes.

Such, in brief, is the present political situation; but it would take a volume to enter into the endless subterfuges, entanglements, and shufflings by which the external Powers strive to gain their ends, and the Albanians tooutwit the lot. A large proportion of the sons of the eagle have always had their own way, and mean to continue doing so.

An unhappy Greek, who held a Government appointment under the 'reform' scheme, said to me in despair: 'What is the use of my staying here? I can do nothing. These people do not want Turkish laws. They simply tell me so. They will yield to nothing that will increase the Sultan's power. When I first came here, I went up into the mountains with four gendarmes as escort to parley with the leaders of a tribe, and to ask them to deliver up certain murderers, that they might be tried and punished according to law. They received me with great courtesy and hospitality. I explained my errand. They thanked me, and said they were perfectly well able to punish their own criminals, and required no assistance from the Turkish Government. I pressed the point. They said: ' " We are fond of visitors, and happy to receive you as our guest. You are welcome to stay here so long as you like as a friend, but if you mean to interfere in our affairs, we beg to point out to you that you are here with only four gendarmes, and every man of us is armed, and we recommend you to return whence you came while you can !" '

I thought so, too. They were very polite, and gave me to eat and drink of their best, and I said good-bye. I have not been there again. We can do nothing! If we sent up troops, there would be terrible bloodshed. These mountain men fight like devils. Probably all the tribes in the North would rise, too. The Turkish Government cannot afford this. These men can neither read nor write, but they know very well how they stand. They have brains, I tell you—they have brains. We have arrested a few, but what is the use? Their friends come to give evidence. I have assisted at the cross-examination of people of very many nationalities, and I have seen nothing like the intelligence of these wild men. They see at once where the question will lead them. You cannot catch them. You may feel certain they are lying, but they baffle you. They have never learned to read, therefore they have memories. They make up the story beforehand; they never forget, and they make no mistakes. Natives of some wild lands are overawed at the sight of officials and men in European costume. These men are afraid of nothing. I confess they are too clever for me. It is true they are savage. They have had to bein order to keep their liberty. When they are no longer obliged to live cut off from the world, they will awake and realize their strength. I assure you they are Bismarcks—veritable Bismarcks. Some day they will demand, and Europe will have to give them what they ask !'

He was so much impressed with the futility of his errand that he talked of throwing up his appointment.

The reform scheme as first put forth provided for the appointment of qualified Christian judges. Until then, under Turkish law, Christian judges were a mere matter of form, and appointed by the local prefect, who could put in any little shopman he pleased, regardless of qualification. They were paid about £25 a year, and their power was nil. Now they are appointed by the Minister of Justice, must be trained lawyers, and receive about £100 a year. There are two Moslem and two Christian judges on the Bench, and the president is Moslem. The Christians can, therefore, be outvoted; but I heard no complaints of this having been unfairly done. The Christians of Turkey have, no doubt, scored by this concession, but in Albania it has given very little satisfaction.

The poorer part of the population is glad when a tyrannical Beg is locked up, but, on the whole, the people look with great distrust on any scheme likely to give the Turkish Government a stronger hold on them. Moreover, it is only in Turk-ridden districts that one hears tales of religious oppression. Once north of the Skumbi, I heard no more talk of oppressed Christians, save in Skodra, the seat of the Turkish Vali.

The Albanian is always an Albanian. The Moslem Serb and the Moslem Bulgar have all sense of nationality swept away by the mighty power of Islam. They are reputed the most fanatical Turks in Europe, and are greatly dreaded by their Christian kinsmen. 'Turk,' it cannot too strongly be said, means in the Balkan Peninsula Moslem, and has nothing to do with race. Many 'Turks' know no Turkish, and talk pure Serb.

With the Albanian it is otherwise. He is Albanian first. His religion comes afterwards. The celebrated fights among the Albanians are always intertribal, or the quarrels of rival Begs. Christians may then fight Christians, and Moslems Moslems. The Christian the Albanian persecutes is the Slav Christian, and this is the old, old race hatred. Of all the passions that sway human fortunes, race hatred is, perhaps, the strongest and the most lasting.

The dread that Europe, under Pan-Slavonic pressure, will give more land to the Slavs has, since the Treaty of Berlin, led to a merciless oppression of the Serbs in Kosovo vilayet, an oppression which is partly vengeance for the loss of Dulcigno.

In the face of a common foe, Moslem and Christian Albania unite. Some nations have a genius for religion. The Albanians, as a race, are singularly devoid of it. Their Mohammedanism and their Christianity sits but lightly upon them, and in his heart the wild mountaineer is swayed more by unwritten beliefs that date from the world's well-springs. Of the primitive paganism of the land little is known, and I have failed to learn what man or men converted this very conservative people to Christianity. Some may have listened to St. Paul himself and to his preachers. For at that time the Slav was unknown, and the neighbourhood of Thessalonica was largely inhabited by the aboriginal race. But the teaching must have penetrated the wilder parts very slowly. Preachers from Salonika bore it across South Albania in course of time, and the wild tribes ceased from human sacrifices and other barbarous rites. But they seem to have taken far less interest in it than did the other converted peoples, who hastened to found independent Churches, and to conduct their services (as is permitted by the Orthodox Church) in the language of the people.

The South Albanians alone neither troubled to do this nor to translate the Scriptures. They left all Church matters in Greek hands, and threw in their lot with the Greeks when the final split between the two Churches took place. The services are still in Greek, and the Bible was not translated into Albanian till the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Recently, with the desire for autonomy, a desire for an independent Church has arisen. It is bitterly opposed by the Greek Patriarch, and the Sultan, who has seen the results of a Bulgarian Church, has refused his consent. Albania has no 'Russia ' behind her to enforce her claims. A large proportion of the priests are Greek, and there is a tendency to replace Albanians by Greeks in the higher posts. Sermons in Albanian are strictly prohibited. This causes great wrath, and I was asked several times to tell the British public that the Greek Patriarch was 'a thief, a liar, and perhaps an assassin !'

'The old people,' said the young, 'say that the Japanese are not Christian, and that the Russians are of our Church. What do we care about the Church? We hate the Russians! Here, I tell you, we are all Japanese !'

The effect of all this is to set on foot a scheme for a Uniate Church, under Austrian protection, which would tend to unite more closely North and South.

In the North matters are diffferent. The mountain tribes which have not turned Moslem have always been faithful to Rome, and have consequently retained much more national independence. But in neither north nor south did Christianity succeed in gripping the Albanians firmly. At the end of the fifteenth century, when Skenderbeg died, they soon came to terms with the Turks, and, mainly to retain freedom, began to ' turn Turk' in considerable numbers: the chieftains' families that they might retain command, and the peasants, who were in contact with the Turks, in order to escape spoliation. In outlying parts they remained Christian, while their Begs went over to Islam.

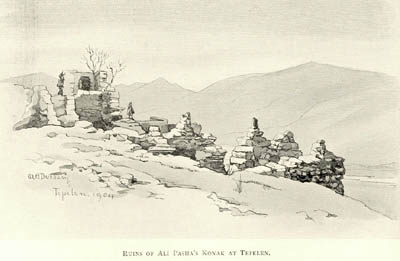

I believe the Mirdites and their Prince are the one example of an entire tribe which has remained Christian throughout. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries conversions to Mohammedanism were, for various reasons, very numerous, and many more were brought about at the beginning of the nineteenth century by Ali Pasha, who, during part of his lurid career, made religion a reason for robbing his Christian subjects of much property.

But the Albanian, even when he appears to yield to circumstances, asoften as not makes them yield to him. He took Christianity very lightly, and Mohammedanism, too, seems to have had but little effect upon him. Many of the people are extraordinarily lax about it; in no place that I know have the Albanians taken the trouble to build a really fine mosque, and there are whole districts where the women are unveiled. Oddly enough, where they are veiled they are veiled extra thickly. A good Mohammedan should turn Mecca-wards and pray five times a day. I have spent day after day with Moslem gendarmes and horse-boys, and never seen an attempt at a prayer. But, on the other hand, once, when passing some soldiers of an Anatolian regiment who were devoutly praying by the wayside, my mounted escort pointed them out to me and laughed as though it were the best of jokes.

Under the veneer of Mohammedanism often lies a thin layer of Christianity. In many villages 'Moslems' still give each other red eggs at Easter, and I have seen them making pilgrimages to a Christian shrine. I am told that some swear by the Virgin. There are often Christians and Moslems in the same family. If a Moslem charm fails to cure they try a Christian one, or vice versa. The cross or the verses out of the Koran are simply amulets. Under all lies a bed-rock of prehistoric paganism, which has, perhaps, more influence in their lives than either of the other two.

The Northern Moslems are Sunnites, or profess to be; but the Moslems of the South all belong to a very unorthodox sect of Dervishes, the Bektashites. Hadji Bektash, variously reported to have come from Bokhara and Khorassan, founded the order early in the fourteenth century. But the Dervish spiritual principles are far older than Mohammed's time, and Hadji Bektash, in so far as he was a Moslem, was a follower, it is said, of the Kaliph Ali.

The present Bektashites, I am told, do not observe the Mohammedan fasts, and trouble very little about the prophet. They are very tolerant of other religions. Jella-a-din, nephew of Ali Pasha, and formerly Governor of Ochrida, had a Christian wife, whom he allowed to go regularly to church, stipulating only that she should be veiled. The teaching is said to be highly mystical and of a pantheistic nature, with a flavour of Omar Kayyam. Lately, I am told, it has been a good deal persecuted, and the Sultan has been workinga Sunnite propaganda. A Governor who went only to the Bektashite 'tekieh,' and not to mosque, would lose his post now. At one place I was told, 'It is better not to talk about it. We are afraid of trouble.'

In the event of a free Albania, it seems probable that many of the sect will turn Christian. For the lower classes, as do most religions, Bektashism supplies a quantity of miracles, and large numbers of lambs are sacrificed at the shrines of popular saints Khizi, a mythical character, who is said to figure largely in Oriental spiritualism, is identified by many with St. George of dragon fame, and the Bektashites keep St. George's Day with ceremony.

The Albanian, in short, stands out in marked contrast to all the rest of the Sultan's subjects. In appearance he usually impresses the stranger very favourably. The 'magnificent Turk' that the Cook's tourist admires in Constantinople is almost always an Albanian. So is the faithful and honest kavas that protects him. When you meet someone who cries up the splendid physique of the Turkish army, you always find he has seen the Albanian regiment.

And alone, of all the Balkan peoples, the Albanian is an artist. His peculiarly indomitable personality always brings him prominently forward. Where he has been handed over with part of the territory to Montenegro he is rapidly absorbing all the trade. When he ceases to obtain money by fighting he does so by commerce. He owns half the shops of Cetinje, and you may find him driving a flourishing trade all the way up the Dalmatian coast, and also in Italy, and in Bosnia.

Commercial travellers who have to do with him will tell you that he understands business, and is reliable. He has, it appears, only to live under a decent Government to prosper.

His aspirations are very great. As the aboriginal inhabitant, he claims all the five vilayets—Kosovo, Skodra, Monastir, Janina, and Salonika. The claims of other peoples also have to be considered, but when the division of the debateable lands takes place it is to be hoped that the rights of the Albanian will not again be ignored, and that his land will be extended eastward. It is said of him sometimes that he has no definite plan of Government, and has not succeeded in obtaining his own independence; but it must be remembered that, though Bulgaria owes her position entirely to outside help, when once started she has done very well. And the Albanian considers the Bulgar 'a thick-headed Scythian.'

CHAPTER X

'Turn we to survey,

Where rougher climes a nobler race display;

No product here the barren hills afford,

But man and steel, the soldier and the sword.'

MONASTIR TO TEPELENIT was two o'clock a m., pitch dark, and freezing hard, when I left Monastir in a large ramshackle carriage, with four horses abreast and a Bulgarian driver, two gendarmes riding ahead as escort, and two Albanians (our assistant at Ochrida and his brother) as travelling companions. The road was frozen into deep ruts, and we were rattled about like dried peas in a pod. As I had had no time to rest since leaving Ochrida, and had been riding all the previous afternoon to make sure my new saddle was all right, I nevertheless dozed till dawn, and dreamed I was on board ship. The pallid sun crawled up, the white fog lifted off the frozen land, and we all got out and walked to thaw our toes.

Leaving Resna on our right, we turned along the western side of Lake Presba. Ploughing was in full swing, and in some fields the young green corn was already sprouting and promising food for the hungry land, and the big lake was extraordinarily beautiful in the morning light. Ochrida is magnificent, but Presba is faery-like in its loveliness.

My comrades held out hopes of a 'han' and a possible fire, where we should rest and refresh at midday, but we arrived only to find it had been burnt down during the late insurrection, and a party of Albanian soldiers encamped in the ruins, as lonesome, melancholy, and comfortless as any Bulgarian refugees. I bought for twopence a very neatly-made wooden spoon, with an ingenious folding handle, from a trooper, who was whiling away the time by carving such from a lump ofboxwood, and producing artistic results with no other tools but a clumsy pocket-knife; for the Albanian is a born arts-and-craftsman, clever-fingered and inventive, with an instinctive sense of design and a power of boldly handling strong colours that rarely fails him.

No fire, no shelter, frozen ground, and a bitter wind. I took refuge in the carriage again, and having had nothing but a cup of black coffee since last night's dinner, ate a whole fowl without any help. Then on again through a pass that was Montenegrin in its wild ruggedness—all loose gray rocks and big box-bushes, whose leaves were nipped red with the frost. Here my comrade pointed out the split in the cliffs whence a band of brigands had swooped down on his brother some twelve years ago, and carried him off into the mountains, where he suffered great hardships for six months as their prisoner. Now, however, the country had been reported safe, and no one had been 'held up ' for two years, for the chief brigand bands had surrendered their rifles and been amnestied.

We zigzagged down a steep and long descent, saw below us the small lake of Malik, the third of the Albanian lake group, whence flows the river Devoli, and reached the big fertile plain. No more wooden, lath-and-plaster houses, but well-built stone ones, with red-tile roofs, neat villages, and scattered on the hillslopes, the big wealthy-looking dwellings of the local

Begs. The land was well cultivated, and the road very fair, and the men by the way walked with a swinging stride, and held their heads up. 'All here is Albanian,' said my comrade, and I felt I was once again in a part of the Peninsula where I felt at home. Part of the population is also claimed by Greece, some is Vlah, and it is clearly not Bulgarian. Nevertheless, part of this land, too, was to have been swept into Russia's Big Bulgaria of S. Stefano fame.

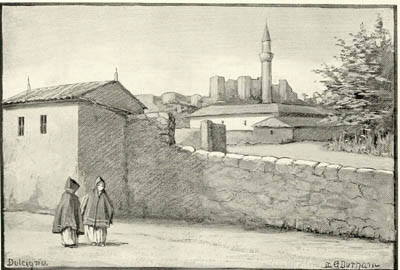

Koritza (Korche, Alb.) is a surprising town. It is clean, really clean—the cleanest town I know in the Turkish Empire—with straight, well-paved streets that are quite free from dogs and garbage. It lies high on a mountain-ringed plain, over 2,000 feet above sealevel, is healthy, and has a good water-supply.

Scarcely more than a third of the inhabitants are Moslem. In the mountains hard by inferior coal is quarried, and the town actually boasts a steam flourmill. Were Korche connected by a railway with thecoast, there is no doubt it would develop rapidly, for the coal is good enough for export. Even with the present difficulties of communication there are a surprising number of foreign goods in the shops. Much of its wealth has been made abroad, for though under present circumstances the Albanian finds it difficult to progress at home, he shows great business capacity in other lands, and proves his patriotism by spending his earnings in his native land.

Korche is the more interesting because writers of forty years ago compare it most unfavourably with Ochrida. But while the Christian population there has been led to disaster by political propaganda, that of Korche has progressed steadily and surely.

Ochrida is still mediæval, but Korche is civilized. I was received with very great hospitality at the Albanian girls' school, which is so much 'up-to-date' that I felt as if I had been suddenly dropped back into Europe. It is the only recognised school in all South Albania in which Albanian children can learn to read and write their own language. It uses the special Albanian, and not the Latin alphabet.

A boys' school, which was started in Korche seventeen years ago, with Government permission, went on very successfully for fifteen years, when the authorities suddenly swooped down, closed it, and imprisoned the masters at Salonika without any form of trial. Korche being one of the places the Greeks wish to annex, the Greek Bishop of Korche objects to the teaching of the vernacular. But the girls' school lives under Austrian and American protection, and has so far weathered all storms.

I called on the Turkish Muttasarif, just to show that I was on a free-and-above-board Government-permitted expedition. He was affable, spoke French, and told me that the population consisted entirely of Greeks and Turks. Albania was a word we did not mention. I might have, he said, as large an escort of gendarmes as I pleased. I told him I believed there was no danger, and one would be enough just to show that I had leave to travel. He heaved a sigh of relief.

' No,' he said, 'there is no danger. Here, thank God, we have no Bulgarians!'

Bulgarians are not beloved in Korche, the trade of which suffered much last year when the roads to Salonika and Monastir were infested by Bulgarian bands, and almost unpassable for many months. Korche was very kind to me. It greeted my plan of riding all through Albania with enthusiasm. The houses I visited were all Albanian; very good houses, too, comfortably and prettily arranged, and at each I was begged to tell England that there are better people than Bulgars to be freed. Here and elsewhere I was distressed at the high hopes raised by the mere fact that someone had come from England to see what the land was really like. Nor were my assurances that I possessed no political power ever of any avail.

The political situation always fills the foreground in the free States of the Balkan Peninsula. In the lands that are yet Turkish it obscures the heavens and pervades all space. Many wanderings had shown it me from the Servian and Montenegrin points of view. I had seen it at Resna and Ochrida through Exarchist and Patriarchist eyes. I knew what it looked like in the vilayet of Kosovo, and was now to be shown it in a new light. You cannot escape it; if you shut your eyes to it some one will rub your nose in it. I stayed a few pleasant days at Korche, and then plunged alone into the unknown.

One a.m. is a dree hour, and though my kind host supplied me with a breakfast of hot milk, I cannot say that I started to explore Albania with much enthusiasm. It was a brilliant, starlight night, and bitterly cold. I said good-bye to all my friends, and started in the same four-horsed carriage in search of the strange man who was to pilot me through a wild land. The road was terribly rough. I dozed unhappily till six, and stared through the white dawn on a lone bare land, as rugged as Montenegro, with narrow cultivated patches in the valleys and great snow-peaks above.

At 9.30 we rattled into Kolonia, a group of tiny houses on a small and lofty plain, ringed round with bleak heights.

My driver, a Bulgar, made me understand we must rest for two hours, and put me down at a forlorn han. The owner showed me up to the empty and unfurnished den which is the cold comfort offered by these hostelries. Albanian was the only tongue spoken. Several people came and stared at me, and retired. Then an officer appeared, the Izbashi. I tried him in Servian, as a sort of forlorn hope. He rose to it at once, for his Mama was a Bosniak. In came the Kaimmakam, in great state, with several police—a mild-looking, elderly man, who spoke only Turkish. The Izbashi translated. I was to go to the Kaimrnakam's house, where there was a fire, and all was very good. So off we went. Arrived there, the Izbashi fetched his Bosnian mama, a funny old girl, who was not veiled, but was particuiar to keep a shawl over the top of her head and carefully pinned under her chin while the Kaimmakam was in the room. Otherwise she did not treat the gentlemen with any respect, but chattered and joked away at a great rate. To entertain me the Kaimmakam produced a Turkish book, with pictures of the Marble Arch and the Bank, and was delighted when I recognised them. I fancy he imagined I resided, when at home, in one or the other. They were exceedingly hospitable, asked whether it was a day on which I ate meat, and insisted on preparing me a meal.

Meanwhile the two men withdrew, and sent their ladies in—the wife of each and several daughters—all closely veiled, giggling wildly and in great excitement. They unwound themselves, and appeared in would-be European attire of the most appalling cut and design. The Izbashi's Boanian mama showed me off, and was so voluble that I did not understand much; but as she greatly preferred doing all the talking, this was of no consequence. Suddenly a hand was heard at the door.

There was a wild seizing of wraps, several shrieks, and a rapid veiling. Even the Isbashi's mama put on her shawl again. The door opened, discreetly, a few inches, and a small boy of four squeezed in. This was considered a vast joke. My lord, who was the Izbashi's only hope, was well aware that he was the sole representative of the superior sex, and gave himself the airs of a Pasha. Cross-legged on the Kaimmakam's couch, he received the homage of the ladies with much dignity and satisfaction, and perpetrated many witticisms at my expense, which were unfortunately lost upon me. More knocks and a parley. The ladies reswathed themselves, and went giggling out again, and, after sufficient interval had been left for their escape, the gentlemen and the dinner appeared. A beefsteak, bread and honey, a glass of wine, and a brand-new knife and fork to eatwith—' quite alla Franca,' as the Izbashi said. They begged me to stay the night, but I made them understand that I was expected at Leskovik.

Kolonia is entirely Moslem, and there are not more than 100 houses. There is little cultivable land in the neighbourhood, and the place, until quite recently, has been famed as a nest of brigands. The present disturbed state of the Turkish Empire has, however, given a good deal of employment to fighting men, and there has been no brigandage in this part for two years. Kolonia treated me, at any rate, very handsomely, and sent me on my way rested and refreshed, and escorted by a fresh couple of gendarmes.

On through a wild, bleak land of gray rock, sparsely inhabited, and for the most part uninhabitable. I grinned when I remembered that, in drawing-room meetings in England, people seriously propose to pen the 'naughty' Albanians into territory of this sort, and ask Lord Lansdowne to make the Sultan see that they stop there.

A huge white wall of snow-clad mountain with an almost level sky-line towered on one hand, grim and impassable. Leskovik, small and stony, hung high on its slope. The Police Commissary and a mounted escort dashed out to meet me, and we clattered into the main street a little before sundown, after a sixteen hours' journey.

The usual crowd gathered to see me, and it was an anxious moment, for here I was to meet my unknown travelling companion, and on him the success of my tour would largely depend. He appeared at once, and took me off to the house of a relative. I owe him many thanks, for though he had never before undertaken dragoman work, he piloted me successfully all through Albania. That I might see the wilds of the land he left his usual business route, and through all the consequent hardships and fatigues he was always cheery and helpful and good-natured.

Leskovik is a quite small place, solid and stony, built much like a North Wales village, but clean and tidy, the population mostly Bektashite Moslems. Some of the Christian women had a small cross tattooed between their eyebrows. There is a small church and a Greek school. The town exports dried meat, the flesh of the mountain sheep, and has to import almost all its corn. Such cultivable land as there is is well worked.

I was now in the vilayet of Janina, which is more under Turkish power than any other part of Albania. Its Vali is much hated, and it is the only one of the three Albanian vilayets I went through in which the Christian Albanians complained of persecution. This arises from the fact that the taxes in this part are farmed out to several powerful and notorious Moslem Begs, who, by exacting double and treble, even ten times, the dues by force of arms, and keeping the difference, find it worth while to support the Turkish Government. I was assured there were plenty of 'good' Begs, but that only the 'bad ' ones had Government appointments.

Nor does the Christian population alone fear persecution. I was given a message to the effect that the Moslems were very pleased that I should visit their town, and were sorry they could not ask me to visit them, but some years ago an Austrian Consul had passed this way, and by invitation had spent the night at a Moslem house. Its master was shortly afterwards arrested and sent into exile without trial. The Kaimmakam, a young Albanian who speaks French well, came to see me twice, and expressed very liberal views. All religions to him were but paths to the same place: we must travel by the road; whether we go by the church or the mosque makes no matter. It is the same God. When he went anywhere he went to mosque, 'but what we have to remember is that we are all Albanians. In England,' he added, 'there are many religions, and people do not kill each other about it.' Poor man ! he thought we were civilized, and had never heard of Passive Resisters. He questioned me about the Bulgarians, and was eager for news. This hatred of the Exarchists for the Patriarchists-—could I explain it? In order to free themselves from Moslem rule, here are the Christians who amuse themselves by killing each other! For himself, he did not like the Bulgarians, but he was sorry for the poor devils of peasants who were the victims of politicians. He asked me to tell him the truth about the state of the burnt villages, and said he was glad someone had supplied food. 'But, I believe,' he added with a smile, 'that they did not make an Exarchist of you ! Mademoiselle, I can promise you that you will find friends in Albania.'

From Leskovik I rode to Postenani, my guide's home, by a rough track through wild mountains skirting round Malesin, a huge isolated sugar-loaf which, sixty-five years ago, was held as a fortress by one of Ali Pasha's Begs, who defended it successfully against the Turk for several years. Finally they discovered and cut off his water-supply, and he surrendered. He had three houses upon it: one at the top, one at the base, and one halfway up. Only the latter remains, and his son, the present Beg, is very poor.

Postenani, a small village, lies very high, with a valley below it and a huge and almost perpendicular cliff towering at the back. It is almost all Christian. My arrival caused great excitement, no foreigner having been there lately, and never a woman; and I was received with the greatest kindness and lavish hospitality. Any amount of visitors called on me, and I paid return visits on all. I am afraid to say how much black coffee, rakija, jam, water, and sweet-stuff I swallowed. They all had to be partaken of in each house. Few houses possessed chairs or tables, but they were comfortable and well-to-do.

The floor, covered with scarlet and black rugs of good design; the walls, panelled with dark wood almost up to the raftered, often well-carved, ceiling, the hooded stone fire-place, with its blazing logs, made a rich setting for the athletic figures of the young men, with their white fustanellas frilling round them, and the handsome women, clad for the most part in dark blue— grave, dignified, sober people, strong, well set up, and healthy. Much ceremony is observed. The young treat the elder with great deference. The women always kissed me, and laid my hand against their foreheads. The elder lady of the house sits with the guests, the son's wife waits on everyone, stands all the time, and leaves the room backwards. The houses were specklessly clean, the boards scrubbed to whiteness, the cups and cooking utensils shining.

The fame of the help given to Macedonia had spread and raised high hopes. Surely, if England had helped the Bulgars they would help the Albanians when they knew their needs. I was distressed by the hopes founded on my visit. One woman declared that good could not fail to come of it.

Brigandage and the Government, I was told, were what they sufferedfrom. The Government robbed them, and gave them no protection at all. The richer men paid armed guards; the others subscribed for two more. They greatly feared the men of the Kolonia district, but vowed I was safe, as there was no one in the village who would betray my presence to outsiders. Were it known, they would probably be raided, as I was worth putting to ransom. Moslems took to brigandage to escape conscription and to gain money to pay for exemption from military service. They were chiefly from rugged districts where there no means of earning enough otherwise.

It was a dog's life in the Turkish army. Many of those who had taken up brigandage were amongst the strongest and most intelligent. In any other land such men would be good citizens. Here they lived like wild beasts on the mountain, and robbed rather than be robbed and oppressed by the Government. Such is brigandage from the native point of view. They dreaded the brigands, but they pitied them, and regarded them as the victims of circumstances. My guide was afraid to travel anywhere with me without a gendarme or two, as, had anything happened to me, he would have been accused of connivance.

I stayed some days with the kindly, simple villagers, many of whom had earned their money, as did my guide, in other parts. There seemed to be a great deal of esprit de corps among them. Those who had money paid taxes for those who had not, and made up the sum due from the village; so also are the dowries for the poor girls subscribed by the community. The women marry at sixteen or eighteen, generally under twenty. The daughter of a well-to-do peasant is expected to bring with her the value of £T100.

Halfway up the cliff, not far from the village, is-a hot sulphur spring, reached by a narrow path hacked in the rock-face, all wet and slippery, with a sheer precipice below, the last pieces very bad, but they drag invalids up it. Two cranky huts are stuck like swallows' nests on the ledge. The water bubbles and rumbles loudly within, and hot steam spouts forth. This is highly esteemed as a rheumatism cure. There is no doctor within miles, and the people prayed me to bring some water to England and have it analyzed to see if it would serve as a cure for other things; but, unluckily, though, after untold escapes, I conveyed a glass bottleful in my saddle-bags all the way to London safely, the analysisfailed, and the poor people will be disappointed.

Poor people, hard - working, living strenuous, dangerous lives in the little oasis they have made among the mountains, who tendered their hospitality with such kingly courtesy, I was sorry to leave them. But time was flying. My guide made up his bale of goods, and the Kaimmakam sent over a couple of 'suvarris' with a polite message that I was to ride one of their horses if I wished. We had one pack and two saddle mules. The 'kirijee'—a tall young fellow in a fustanella, with a very large sheath-knife as long as a Roman sword—strode alongside and took rides on top of the pack now and again.

Loading up and farewells took some time, but at last we were off into the heart of the mountains, away over great loose stones, through wildly magnificent scenery, barren and lifeless, like the bones of a dead world; then over the pass and along a hoof-wide track high along the mountain-side. Down far, far below lay the valley of the Viosa, green and fertile, 'all a-blowing and a-growing,' and the heights beyond were fiercely blue.

The leap from winter and the wilderness to spring, and colour was dazzlingly sudden. Had I been a poet I should have written a verse about it. The sunshine warmed the heart of the pack-mule; he sang aloud, leapt with all four feet at once off the ground, wagged his tail, lashed out freely, and played like a lamb upon the giddy brink.

The descent was far too abrupt for riding. We scrambled down somehow, and got to the bottom in an hour. Halfway down, in a copse, was a tiny stone chapel, now disused, as all the neighbouring tiny villages have turned Moslem. I was told, however, that it was miraculously protected, and no one dared cut wood near it. This was evidently true, for the trees were the largest in the neighbourhood. The villages scattered about the mountain's foot were mere groups of ten or twenty cottages, but all stone, and solidly built.

In the valley we struck the highroad, such as it is, and waiting by the bridge I spied military, and found, to my disgust, that two officers and three troopers had come to meet me. Leskovik had warned Permeti of my approach. A military escort almost always means you are 'suspect.' Gendarmes will obey orders, and are often most obliging and useful on rough tracks. Officers are quite unmanageable and very expensive. A military escort also is a great expense to the village on which it is quartered.

All the relief agents and correspondents in Macedonia had been more or less haunted by the army, excepting only myself. To have evaded it there, only to encounter it when out on 'the spree' in Albania, was humiliating.

Entering the town with this bodyguard caused crowds to turn out to see me. It was as bad as being a wild-beast show or the Royal Family. I was conducted to a house where the Kaimmakam had arranged that I should stay. More than this, a soldier was put on guard at the door of my room to keep perpetual watch over my doings—a cheery polyglot youth whose business it was to bob in with every Christian visitor and overhear the conversation. As an officer was told off to accompany me wherever I went, I was practically a prisoner. I could not go out for a stroll without such a parade that crowds thronged to see me. I could not sit in my room without my hostess, a Greek, thinking it polite to keep me company. As I understood no word of her conversation, and she always stood up whenever I moved, and as, so my guide told me, the presence of the soldier made her very nervous, the position was most embarrassing.

I had been quartered on the poor lady quite against her will. I think she was selected because she was Greek, with a view to proving to me that it was a Greek town. The room was very swagger with European carpet and furniture, a lamp and looking-glass tied up in gauze, and Berlin woolwork, virulent enough to have been made in Germany, which glared from every corner and hung framed on the wall. In spite of this gallant attempt at being European, the bed was, as usual, spread upon the floor when night came. The soldier ate up the remains of my supper, and slept just outside my door.

I paid a state call on the Kaimmakam next day— that is to say, I was told at what hour he wished to receive me, and was fetched by an officer. The Kaimmakam is very much a Turk, and comes from Asia Minor. His civility was extreme and his French very fair. He was entirely at myservice, and no honour was too great for me.

He dismissed all the other men, sent for his wife and mother, who spoke only Turkish, and started crossexamining me, but was not clever at it. I knew that Albania was disaffected, but I had not till then realized that the Turkish Government was so nervous about it. 'Bless the man !' thought I, 'the political situation must be uncommonly " tittupy." ' It was my first, but by no means my last, experience of being 'suspect'' and I was amused. The Kaimmakam eyed me keenly all the time, piled on questions, and supplied information. The inhabitants, he said, were all Greek.

'They nevertheless speak Albanian, do they not?' said I.

'Malheureusement,' said the Kaimmakam sadly.

He added vaguely that they had somehow learnt it ! Many even imagined that they were Albanian. This was a pity, but with plenty of schools the matter would soon be set right!

I said that to an English person it was a sad and strange thing that people in the Balkan Peninsula scarcely ever knew what they really were. He agreed it was 'tres triste'; it was all caused by lack of education. With schools, in a few years, they hoped to set everything right! Thus he, too, was playing the old, old game of trying to prop Turkish rule by rubbing one race against another. I wondered how much he believed of what he told me. We talked about the blessings of education. I deplored the terribly dangerous state of the country—that even a town like Permeti was unsafe. Horror on the part of the Kaimmakam---no danger at all—'parole d'honneur.'

'Then there is no need for that soldier to remain at my door?'

This was unexpected. The Kaimmakam smiled sweetly.

'The soldier,' he explained, ' was not there to protect me, but merely because of my high rank.'

' Alas, monsieur ! I am not a Princess—you mistake: I am of the lower classes. In England I am nobody ! I am not accustomed toceremony, and it troubles me.'

' You do not understand, mademoiselle. This soldier is simply to do you honour,'

' I understand very well, monsieur. You think I am a spy.'

The Kaimmakam was horrified. The soldier was my servant, and I could command him.

I said good-bye to the Kaimmakam and returned to my lodging. There I told the soldier to go. He saluted cheerfully, and departed. In ten minutes he was back again, and said that the Kaimmakam said he was to wait for further orders! I gave it up, and reflected upon the political situation. I was sorry for the Kaimmakam, for he had given the show away, rather badly.

The leading Christians of the town all called on me, and were most polite. The presence of the soldier explained their position with silent eloquence. He and a police officer walked on either side of me, and helped me to pay return calls on the Christians. It was just before Easter, and the Christian houses were in the agonies of the 'spring clean,' which is in reality nothing more nor less than the Easter purification. Every room has to be scoured and whitewashed. The gipsy women of the town served as painters— swarthy, bright - eyed things in baggy breeches, as active as monkeys, who rushed about wielding their whitewash brushes with the greatest glee, chattering gaily the while. Not that the houses looked as if they required doing up; they were specklessly clean to begin with. The Dutch are said to be the cleanest housewives, but I believe the South Albanians would run them hard.

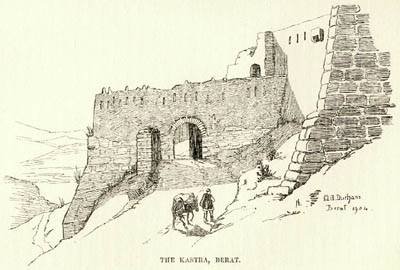

The town is clean, well built, and most beautifully situated on the edge of the blue-green Viosa, which tears through a gully it has cut for itself in the loose soil. There are 7,000 inhabitants, three mosques, three churches, a Christian girl and boy school, and a Moslem boy school. A huge isolated rock, a fragment fallen from the mountain above, lies out boldly by the river's edge, crowned with the ruins of a monastery, the dwelling-place of some forgotten saint, and a spring of holy water flows from its base. On the hill just above is amass of ruined walls, all that is left of the fortresses built in Ali Pasha's time. Perhaps it was because I came to it out of stones and barrenness that, as I saw it from the ruins of Ali Pasha's fortress, Permeti, with its tall cypresses, purple Judas-trees, and delicate spring greenery, seemed one of the fair spots of the world. But it is on the edge of the wilderness, and the soldier threw back his head and yowled aloud, to imitate the wolves of a winter's night when the snow is deep on the mountain. Permeti, too, had a due respect for the capabilities of Kolonia, and remembered the day, twenty years ago, when a band had swept down and carried off a Moslem maiden, the fierce fight, and the struggle in the then bridgeless river which drowned several of the combatants.

The Kaimmakam duly returned my visit. An officer entered my room salaaming, and announced that Kaimmakam Beg was about to visit ' Mamzelle Effendi.' I understood the two titles; the rest was in Turkish. Enter the Kaimmakam at once. He had been telegraphing industriously, and found out quite a lot about me. Said I had come all the way from Korche to Leskovik without a dragoman. He was amazed. I said it was nothing for the English. The fact that I had been giving relief in Macedonia weighed heavy on his soul. So many lies, he said, had been written about Turkey, that he was very anxious that I should hear nothing but truth; therefore he sent officers with me. I had come alone to learn the truth for myself, and he was doing his best to assist me. The 'truth,' of course, was that all parties were feverishly anxious for my suffrages.

The paying of compliments caused me much wear and tear. I put one on with a trowel; he piled on several with a spade. I found it impossible to put them on thick enough. The other party always went several better. The gist of it all was that no pains were to be spared to teach me the truth about Permeti. It is doubtless the rarity of that article in the Turkish Empire which makes the officials value it so highly. I sallied forth again, this time with a young Albanian officer, a cheery youth most anxious to show off his country.

We proceeded to explore things Moslem. In a little garden, hedged round bytowering cypresses, lay the tomb of a holy Bektashite Dervish; here the good man had lived and died, and the spot is holy and works miracles. He was beheaded and died a martyr, but he picked up his head and carried it back to his garden. Of the respect in which he was held there was no doubt, for the grave was strewn with small coins, and a little wooden money-box was hung on the wall, and the spot was quite unprotected, save by the good man's spirit. Seeing that I was interested, the young officer, no doubt a Bektashite himself, at once offered, to my great surprise, to take me to a 'tekieh' (Bektashite monastery) that lay high on the hillside, above the town—a rich tekieh, so he said, owning wide lands and sunny vineyards.

It was a small, solid, stone building with a courtyard in front. At the entrance we waited while the officer went in to interview the 'Baba' (Father). My Christian guide doubted that we should be let in. We were, however, requested to go round to the back-door, and soon told the Baba was ready. In we went, to a bright little room with a low divan round it, and texts in Arabie on the walls, and big glass windows that commanded a grand view of all the valley.

The Baba entered almost at once, a very grave and reverend signor in a long white robe; under which he wore a shirt with narrow stripes of black, white, and yellow; on his head a high white felt cap, divided into segments like a melon, and bound round by a green turban; and round his waist a leathern thong fastened by a wondrous button of rock crystal, the size and shape of a large hen's egg, segmented like the cap and set at the big end with turquoises and a red stone. He was very dark, with piercing eyes, shaggy brows, gray hair, and a long beard.

Courteous and dignified, he thanked me for visiting a humble Dervish, and prayed that the Lord would protect me now and always, and teach me much upon my journey. He seemed to imagine I was on some sort of mysterious quest. I regretted deeply that I could not talk with him direct, as he sat there and expressed religious sentiments with impressive dignity.

'A man,' he said, 'must always do his duty, though he never lived to see the results. Those that come after him will benefit by his work. But we are all born either with a good or a bad nature. It is our fate. A man, though he work ever so hard, his work is vain if his nature be bad.'

He asked a good many questions about my journey, and seemed genuinely pleased to see me. After he had given us coffee he said that, as it was the first time I had ever visited a Bektashite tekieh, perhaps I should like to see all the building. There were two other small dwelling-rooms. A priest and a pupil lived with him; their life, as I could see, was very simple, he said. They had many men to till the fields and make the bread. Giving bread to the needy was one of the duties of the monastery.

He led us to the kitchen, a fine room with a huge fire-place, arched over by a stone vault carried on four columns. Rows and rows of great loaves were laid out on benches, and more were being made.

Lastly, he showed the chapel. Of this I had but a passing glimpse from the doorway, for he did not invite me to enter. It had a divan round three sides of it, and an altar with candlesticks at one end, and was quite unlike a mosque.

When we left he showed us out at the front-door, shook my hand three times, said a long blessing over me, and hoped that I should be led that way again. I thanked him and he thanked me, and we parted. The young officer was greatly pleased with the success of the visit, and appeared to reverence the Baba greatly.

Tepelen was to be my next halting-place, and as it was about a ten hours' ride, I arranged to leave early. I reckoned without my host, however. Kaimmakam Beg was going to pay-a final call on 'Mamzelle Effendi,' and though ready packed, booted, and saddled, I had to wait. After some hours Kaimmakam Beg sailed in, gay with a bright pink shirt. He had inquired overnight how much escort I would like, and I had asked for one suvarri. He now informed me that, in consideration of my exalted rank, he had decided to give me soldiers, but I could not start to-day because it was raining. Also that he was going to telegraph to Tepelen that I was to be quartered in a private house.

My unlucky hostess had been kept in a constant nervous twitter by the presence of soldiers and officers; all her relatives and children had haunted my room perpetually with the best of intentions, and I had had nomoment of privacy. I did not wish on my tour to be a nuisance to everybody with my soldiers. I told the Kaimmakam firmly that it would be useless to make ready a room for me. I was not accustomed to any ceremony, and should go the han. As for the rain, it often rained in England. I thanked him for all he had done for me, said I should start at once, and soldiers were unnecessary. He agreed; but no sooner was I mounted than up came an officer, the Commissary of Police, a trooper, and two suvarris! They were not pleased, for by this time it was raining hard, and it rapidly got worse. We rode along the valley of the Viosa. It is supposed to be carriageable, but, as all the bridges have fallen, is not. Through the sheets of gray rain, snow-clad peaks loomed dim on either hand, with tiny villages clinging to the lower slopes, and many Bektashite tekiehs. Then the rain became a fusillade of water, and cut us off from all the world. The icy torrent lashed and stung my face and blinded me. I shut my eyes tight, set my teeth, hung on to the saddle-bow, and trusted to the mule, buoyed up always by the hope that I should tire out the military escort.

At Klisura the valley narrows to a gorge. Perched on the great crag that commands it is the huge konak of a mighty Beg, son of one of Ali Pasha's Begs, till two years ago, so the tale runs, the curse of the neighbourhood. He seized everything—mills, farms and stock--levied blackmail freely, and tyrannized over the population, who complained so bitterly of him to the Government that he is now under trial at Constantinople. The konak was passing rich, rumour said. All the nails that went to the making of one room were of pure silver, and in Ali Pasha's time the Beg possessed enough silver-mounted weapons to arm 300 men. It showed, dim and mysterious through the rain, a fit stronghold for a wild chieftain in a wild land. High above, veiled in the clouds on the very mountain-top, lay the ruins, I was told, of King Pyrrhus's castle. Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, and lord of all this land in the brave days of old, and still celebrated here.

We rode into the han at the mountain's foot, a desolate place witha few bare, dirty rooms, in one of which I had a fire lit; my guide, the kirijee and I steamed while we ate the eggs and bread we had brought with us. The military escort meanwhile drank rakija freely, and blew out itself and its horses down below, and ran me up a fine bill, which had to he paid. 'Honour' is a very expensive thing. My guide, who was used to getting about the country at a franc or two a day, was much distressed.

I was to have been met by more military at this point, but they had not turned up. The lot that had come with me were soaking wet, and said it was impossible to go on. I mounted, rode through them, and waved good-bye, which surprised them, as they seemed to expect backshish as well as their bill. As I knew I had paid enough for them to booze on for the rest of the day, I went straight ahead into the rain; the two suvarris followed me, and that was the end of my first and last military escort.

The ride through the gorge should have been magnificent, but all was drenched and blotted in a torrent of rain. The river was full and wide. Thick and muddy, it whirled along, carrying trees and branches; here and there a clean stream rushed into it from its rocky banks with such violence that it made a whirl of clear blue-green in the muddy torrent.

'The Viosa is a wicked river,' said the kirijee. 'From source to mouth it turns no mill, it does no work, but much destruction every year. It has but one redeeming point: it drowns many Turks. Perhaps that is what it was made for. Who knows?

Thunder crashed on the hills, and echoed and re-echoed far away down the valley. The water streamed off my cloak. The road was too heavy for us to get up more than a trot. I began to wonder whether choking off a military escort were worth the price. We seemed to be constantly dismounting, dragging our beasts down gullies and up the other side (for the stone bridges that should have spanned the tributary streams had, every one, fallen), remounting on a wet saddle only to dismount again and clamber over a heap of boulders that had fallen from the mountain-side. Some of these, judging by the bushes rooted between them, had blocked the way for years; but on the maps it is a carriageable road. My companions explained to me that, previous to the Treaty of Berlin, the road-tax was paid in labour and the roads were passable. Byway of ' reform,' a money tax was substituted. It has been collected ever since with praiseworthy regularity, and the roads remain untouched. Such bridges as existed in the neighbourhood were built by a wealthy Beg at his own expense.

We had had about eight hours of this, and I was beginning to wonder how many more I could stand, when a mosque and some ramshackle houses showed ghostly through the downpour; the leading suvarri turned his horse into an entrance, there was a parley, and I slipped out of the saddle and followed him into a little dark drink-shop, smelling strongly of petroleum, and crowded with dripping men. We were at Dragut, and this was the han and general shop. The river, we were told, was a raging torrent; we could not reach Tepelen that night; no boat could take us over. The han was crowded because the folk who had tried to reach the bazar to-day had all returned from the ferry, unable to cross. We must pass the night here. It was a dree hole—dark, chill, foodless, fireless. I wondered why I had come, and only a belief that it was not my Kismet to die in Albania cheered me up. We asked for a fire, and drank rakija.

After a weary twenty minutes the 'hanjee' took us up to a room he had made ready. An icy draught blew through its glassless windows, and our breath steamed in the chill, damp air; there was a piece of matting on the floor, and a tiny tray with a few hot ashes in it. That was all. I was dismayed. The hanjee vowed this was the best room in the house, and that he had no fire-place. We crouched miserably over the wretched little 'mangal '; it did not give enough heat to thaw our fingers, and our clothes were dripping. I looked at the smouldering bits of charcoal with desperate interest, saw they had been but freshly chipped off, and knew that they must have come from a burning log not far away. And that log was the only thing in the world I wanted. The hanjee then confessed to the fire-place, but said it was in his storeroom, which was full of goats' hides, and not fit for me.

It was in truth a melancholy spot. There was a large hole in the roof, through which the water was trickling. It was half full of sacks and onions, piled into a corner to be out of the wet, and all the walls were hung with smelly, gamey, half-dried goats' hides. But there was the hearth-stone, with two smouldering logs upon it. I don't believe I was ever half so glad to see anything. We soon had a blazing fire, called in the drenched gendarmesand kirijee to dry at it, and steamed gaily till the room was foggy, took our boots off, and roasted our feet. My cloak, which hung on a nail, still dripped so that it made puddles. Outside the rain turned to driving sleet.

A neighbour came in and very kindly offered to let me spend the night in his harem, but I did not feel equal to being stranded, tired and damp, among people of whose language I scarcely knew a single word, and, moreover, I clung to the fire-place. I might be given a chilly little room all to myself with a little pan of charcoal in it. I had not the nerve for this, and shocked the poor man's sense of propriety, I fear, by electing to sleep alone in a house full of men. The hanjee supplied coarse maize bread, and with three eggs, 'maggi,' and an onion from the heap in the corner, I made by far the best soup I ever tasted.

An interesting dispute arose when supper was over. The gendarmes were of opinion that the hanjee was a well-known bad lot, and that I could not sleep safely in his vicinity. The hanjee was certain the gendarmes were desperate characters, and I must avoid their end of the building. As I meant to sleep by the fire whatever happened, I took no interest in their moral characters. The waterproof sheet had kept the blankets quite dry, which was all I cared about, and there was a dry patch on the floor large enough to hold me. The hanjee gave me a tree-stem to bolt the outer door with, which seemed rather superfluous, as there was a quite unfastened trap in the floor. I heated the blanket at the fire, rolled up tight in it, slept for eight hours without budging, and woke to the blank misery of gray dawn, gray ashes, a wet floor, and a lean white cat chewing a corner of goat-hide.

I tried to stand, and found, to my horror, I was locked up with rheumatism all down one side from ankle to waist. 'Oh you silly fool !' said I to myself; 'and you thought you understood roughing it !' As a matter of fact, it is usually a mistake to imagine one understands anything. I swallowed a large and indefinite dose of salicylate of soda, washed down with neat brandy, for the muddy dregs of water in the pitcher were too dirty to drink unboiled. I hauled myself on to my feet painfully, and unbarred thedoor. Things were a bit more cheerful when the fire was rekindled, and we breakfasted on maggi and the remains of last night's bread.

The hanjee produced his little bill, which included 3s. 4d. for my bedroom. When I explained that for a smaller sum in Montenegro I had had meat, bread, wine, coffee, and rakija as well, he truthfully replied that Montenegro was a very different place. As, however, he charged an unhappy peasant 2 francs merely for sleeping in the common room without any fire or food, I did not fare so badly.

The sun was shining when we rode out, and the place looked exquisitely beautiful; purple Judas-trees in full bloom, in subtle harmony with the silver-gray olive-gardens, showed it could be hot sometimes. But the snow had fallen in the night and lay low on the mountain-sides; it was dank and chilly till the sun gained strength, and every step of my beast sent a thrill of pain running up and down one side of me from ankle to hip joint.

An hour brought us to the Viosa, with Tepelen majestic, high on its further bank, fortified by big stone walls, loop-holed and buttressed, builtby Ali Pasha, and left unfinished at his death. I had plenty of leisure to contemplate it. The swirling, whirling river raged in a turbid torrent, foaming between the eight buttresses of the broken bridge; on the hill beyond was a crowd that bawled and yelled. One of my suvarris put his hands to his mouth and roared. A reply came bellowing back. The river had begun falling, and perhaps in three hours would be passable; at present the ferry couldn't come at any price.

We unloaded the pack-mule and set the beasts grazing. Several natives joined us in the hopes that a special effort would be made to take me across, and that they might profit by it, and I heard the story of the bridge. It was smashed by a great dood in winter six years ago, and ever since the town had suffered bitterly. Most of its fields lie on the further side of the stream, and this is impassable for a large part of the winter. Then the land can neither be tilled nor sown.

One of my suvarris owned a large piece, and had made a living out of it. Since the bridge fell he was unable to do so, and had been obliged to join the police. There followed the old dismal story of arrears of pay. All thecompany prayed me to help them.

'If you would only do so,' said a man, 'you would give happiness to hundreds of people.'

Many people, I was told, had offered to subscribe towards the rebuilding, and they had vainly petitioned Constantinople again and again. Forty or fifty people were drowned yearly trying to ford when the river is low to save the cost of the ferry, but when they had wanted to try and build a temporary wooden bridge across the still-standing buttresses, they had been forbidden, and told bridges belonged to a Government department. They were terribly in earnest about it.

A Moslem vowed that all I had to do was to write to the Sultan and say I would do it myself. I said I had not money to build bridges.

'It will cost you only a postage-stamp,' he said. 'You must write and say that the sight of the suffering of his Moslem subjects has made you, a woman and a Christian, undertake to help them. A woman and a Christian! It will be such a terrible thing to the Padishah to be offered help by a female giaour, he will order the bridge to be built at once! But you must write from England. He receives all the letters that come from foreigners. Our poor petitions he never sees !'

The Sultan, someone added, was afraid of the English; he allowed them to do anything: 'See what they have been doing in Macedonia! You can help us if you will.'

The relief work in Macedonia was intended to be non-political and purely humanitarian; indirectly it had great political effect, as I learnt daily, and inspired wild hopes in the Sultan's land alike among Moslems and Christians—hopes so great that it dawned upon me gradually that nothing but abject fear could have ever forced His Majesty to have permitted that work to be carried out. Were it not for the misery of the mass of his subjects, of all sects, there are times when I should feel sorry for that terror-stricken man clinging madly to his decaying power in Yildiz Kiosk, a prisoner in his own house, while his moon, no longer ' crescent,' wanes pallid in a pool of blood.

I stared at the gaunt wreck of the broken bridge, the wild mountains, the lone, lorn land. It had come to this: I, a 'female giaour,' was asked to shame the great Padishah by one of his Moslem subjects. The irony of things can scarce go further. Their insistent belief in my power would have made me believe I was the British Empire had not the burning, grinding pain in my leg reminded me I was only myself, and helpless to bear the intolerable weight of the 'white man's burden,' which everywhere the people strove to thrust upon me. And this was at the birthplace of Ali Pasha—of Ali, Lord of South Albania, the Lion of Janina, gorgeous, glorious,brutal, barbarous—invincible Ali, whose rule reached from Arta to Ochrida, and who was only overpowered and slain when he had reached the age of eighty. Where art thou now, oh Ali Pasha? Thy people cry for help to a female giaour !